Zea mays

Zea mays L.

| Ordre | Poales |

|---|---|

| Famille | Poaceae |

| Genre | Zea |

2n = 20

Origine : Mexique

sauvage et cultivé

| Français | maïs |

|---|---|

| Anglais | maize (Grande-Bretagne), corn (Amérique du Nord) |

- l'une des céréales les plus importantes au monde

- 8 types connus, dont le maïs-grain (corné-denté), le maïs doux, le maïs à éclater.

- amidon de maïs : nombreux usages en alimentation humaine et animale et en industrie

- produits traditionnels : tortillas, chicha, pozole, tamales, pop-corn

- produits modernes : pains, corn-flakes, amidon modifié, sirop de glucose, huile de maïs, plastiques

- médicinal : styles

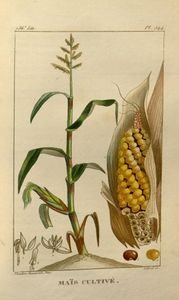

Description

- plante herbacée annuelle, dioïque, atteigant 2 m de haut (jusqu'à 9 m)

- feuilles disposées sur deux rangs, linéaires lancéolées

- panicule mâle terminale ; 1-2 épis femelles latéraux, à 8 rangs de fleurs ou plus, enveloppés dans de grandes bractées laissant pendre de très longs styles

Noms populaires

| français | maïs; blé d'Inde (Can) |

| créole guyanais | mi (Pharma. Guyane) |

| wayãpi | awasi (Pharma. Guyane) |

| palikur | maiki (Pharma. Guyane) |

| anglais | maize (RU) ; corn, Indian corn (Etats-Unis) |

| allemand | Mais |

| néerlandais | maïs, turkse tarwe |

| italien | granoturco, granturco, mais |

| espagnol | maíz |

| catalan | blat de moro, dacsa, panís, panís de l'Índia, blat de l'Índia, milloc, milloca, moresc |

| portugais | milho |

| polonais | kukurydza |

| russe | кукуруза- kukuruza |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

- Voir l'étymologie de Zea

- Maïs vient du nom taïno (Hispaniola) de la plante. Zea a été choisi par Linné, et désignait l'amidonnier en latin classique et en grec.

Classification

Zea mays L. (1753)

Zea mays L. subsp. mays est le maïs cultivé. Par ailleurs, deux types de téosintes sont classés comme des sous-espèces de Zea mays. La coque de leur fruit est triangulaire, alors que chez le maïs cultivé elle subsiste, réduite et vide, à côté du caryopse.

subsp. mexicana

Zea mays L. subsp. mexicana (Schrader) Iltis (1971)

synonymes :

- Euchlaena mexicana Schrader (1832)

- Zea mexicana (Schrader) Kuntze (1904)

Panicule mâle robuste de 1-20 branches, à épillets de 7,5-10,5 mm de long. Fruits de 6-10 mm de long. Cette sous-espèce groupe trois « races » allopatriques endémiques du plateau central mexicain (races Chalco, Durango et Central Plateau).

subsp. parviglumis

Zea mays L. subsp. parviglumis Iltis et Doebley (1980)

Panicule mâle délicate de 1-65 branches, à épillets de 4,5-7 mm de long. Fruits de 5-8 mm de long. Cette sous-espèce est divisée en deux variétés : var. parviglumis (race Balsas) et var. huehuetenangensis Iltis et Doebley (1980) (race Huehuetenango), sur les piémonts pacifiques du Guatemala et du sud du Mexique.

subsp. mays

Zea mays L. subsp. mays est le maïs cultivé. Par ailleurs, deux types de téosintes sont classés comme des sous-espèces de Zea mays. La coque de leur fruit est triangulaire, alors que chez le maïs cultivé elle subsiste, réduite et vide, à côté du caryopse.

Les maïs cultivés se classent traditionnellement en groupes de caractéristiques technologiques et morphologiques similaires. Il n'existe pas actuellement de classification sur d'autres bases.

Groupe Tunicata

| français | maïs vêtu, maïs tuniqué |

| anglais | pod corn |

Groupe Amylacea

synonyme :

- var. amylacea Bailey (1902)

| français | maïs tendre |

| anglais | soft corn |

| allemand | Stärkemais |

| espagnol | maíz amiláceo |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Aorista

synonyme :

- convar. aorista Grebensc. (1949)

| français | maïs corné-denté |

| anglais | flint-dent corn |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Ceratina

| français | maïs cireux, maïs waxy |

| anglais | waxy corn |

| allemand | Wachsmais |

| italien | mais ceroso |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Dentiformis

synonyme :

- var. indentata Bailey (1902)

| français | maïs denté |

| anglais | dent corn |

| allemand | Zahnmais, Pferdezahnmais |

| italien | mais dentato |

| espagnol | maíz diente de caballo, maíz dentado |

| portugais | milho dentado |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Indurata

synonyme :

- var. mays

- var. indurata Bailey (1902)

| français | maïs corné |

| anglais | flint corn |

| allemand | Hartmais |

| italien | mais pietra |

| espagnol | maíz amarillo, maíz morocho |

| portugais | milho córneo |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Microsperma

synonyme :

- var. everta Bailey (1902)

| français | maïs à pop-corn, maïs perlé |

| anglais | popcorn |

| allemand | Puffmais |

| néerlandais | pofmais |

| italien | popcorn |

| espagnol | maíz chapalote, maíz de palomitas, maíz palomero (Mexique) ; maíz reventón (Argentine) |

| portugais | milho pipoca |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Groupe Saccharata

synonyme :

- var. rugosa Bonafous (1836)

- var. saccharata (Koern.) Aschers. et Graebn. (1898)

| français | maïs doux, maïs sucré |

| anglais | sweet corn |

| allemand | Zuckermais |

| néerlandais | suikermaïs |

| italien | mais dolce |

| espagnol | maíz dulce ; choclo (Argentine) |

| portugais | milho açucarado |

- Voir les noms dans toutes les langues européennes

Cultivars

Histoire

- On trouvera une synthèse détaillée sur la diffusion du maïs en Asie dans Desjardins & McCarthy.

- Voir Corn in Buffalo Bird Woman's Garden Recounted by Maxi'diwiac (Buffalo Bird Woman) of the Hidatsa Indian Tribe (ca.1839-1932), edited by Gilbert Livingstone Wilson (1868-1930). Originally published as "Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians: An Indian Interpretation" by Gilbert Livingstone Wilson, Ph.D. (1868-1930) Minneapolis, The University of Minnesota (Studies in the Social Sciences, #9), 1917. Ph. D. Thesis. Récit passionnant de première main.

Cinteotl, dieu du maïs, face au royaume de la mort (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 11)

tlatatacani, homme avec un bâton à fouir, face à des plants de maïs en terre (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 29)

Chalchiuhtli icue, déesse de l'eau, versant de l'eau (colonne de gauche) sur un pied de maïs (image du milieu) (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 33)

un dieu aidant le maïs à pousser (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 34)

Tlaloc, dieu de la pluie, aidant le maïs à pousser (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 34)

Cinteotl, dieu du maïs (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 34)

Tlacolteotl, déesse de la terre (à gauche) et Patecatl, dieu du pulque (à droite) (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 35)

Chicomecouatl, déesse du maïs (à gauche), et Cinteotl, dieu du maïs (à droite) (Codex Fejérváry-Mayer 36)

Sahagún, 1540-1585, Historia general de las cosas de nueva España.

Sahagún, 1540-1585, Historia general de las cosas de nueva España.

Sahagún, 1540-1585, Historia general de las cosas de nueva España.

ZARA, PAPA HALLMAI MITA. Janvier : maïs, temps de pluie et de butter le maïs, p. 1132. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARAP TVTA CAVAI MITAN. Février : temps de surveiller le maïs la nuit, p. 1135. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARAMANTA ORITOTA CARcoy mitan. Mars : temps d'épouvanter les perroquets hors du maïs, p. 1138. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARA PVCOI ZVVAMANTA uacaychay mita. Avril : maturation du maïs, temps de le protéger des voleurs, p. 1141. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARA CALLCHAI ARCVI PAcha. Mai : temps de faucher et gerber le maïs, p. 1144. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

PAPA ALLAI MITAN PAcha. Juin : temps de l'arrachage des pommes de terre, p. 1147. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARA PAPA APAICVI AIMOray. Juillet : mois pour rentrer le maïs et les pommes de terre récoltés, p. 1150. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

HAILLI CHACRA IAPVICVI pacha. Août : chants de triomphe, temps de retourner les terres, p. 1153. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARA TARPV MITAN. Septembre : cycle des semailles du maïs, p. 1156. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

CHACRAMANTA PISCO carcoy pacha. Octobre : temps de surveiller les semis dans ce royaume, p. 1159. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

ZARA CARPAI, IACO MVCchoy rupay pacha. Novembre : temps d'arroser le maïs, de la sécheresse, de la chaleur, p. 1162. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

PAPA OCA TARPVI PACHA. Décembre : temps de semer pommes de terres et ocas, p. 1165. voir original et commentaires sur Site Guaman Poma

Usages

- Voir les Plantes médicinales de Cazin (1868)

Worldwide cultivated as a cereal and forage grass. Main producers are the USA (about 50% of the world production), SE Europe, Russia and the New Independent States (CIS), Italy, China, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Argentina, India, and Indonesia. W Europe and Japan are the main importers. In Central America maize had been the most important human staple cereal food since thousands of years, usually ground into flour for bread, cakes, and mash. In parts of Africa it became a staple during the 19th centuries. Because it is deficient in some essential amino acids, it must be supplemented by other food to avoid deficiency diseases. Maize grain is also one of the most important kinds of feed for intensive livestock breeding in developed countries. It is also processed into starch, syrup, sugar (glucose and maltose), edible oil from the germ, and more recently also into corn chips and tortillas as part of breakfast cereals. Many more specialised products are produced from maize grain constituents such as furfural, acetone, butyl alcohol, and different small ingredients used in the food industry.

Whole immature cobs are commonly used as vegetables, and very small ones are often served as a cocktail or gourmet dish. In the USA and Canada, "sweet corn" represents a remarkable part of the total corn market. Here mainly special cultivars are used where the conversion of sucrose to starch is more or less blocked. Improved "supersweet" hybrid cultivars have been developed more recently. Maize is also particularly grown as a green forage for livestock, and approximately since the begin of 20th cent. also for silage, especially in cooler temperate areas. Dry stems and leaves are suitable as feed and can be used for paper pulp.

Currently most of the high yielding fodder and grain cultivars are hybrid or double-hybrid strains because maize shows especially high heterosis effects. Further elevation of the protein quality is one of the main breeding objectives. Scientists continue to debate the ancestry of corn. The area of domestication was probably S Mexico (between Chiapas and Mexico City) where remains have been uncovered (dated at appoximately 5.000 BC) which are true corn with all of the characteristics of modern corn except size. Such plants have never been found in recent time. Therefore the most logical conclusion "the ancestor of corn was corn" (Mangelsdorf 1974) cannot be simply substantiated. Another theory regards annual teosinte as the ancestor. However, known remains of annual teosinte are not older but mostly much younger than those of maize. This could be explained if Z. mexicana subsp. parviglumis was the ancestral teosinte taxon as enzyme characters and first molecular data suggest (Doebley 1990). Most recently, a proposal that the maize cob arose by "sexual translocation" (Iltis 2000) from the terminal central spike of the male teosinte tassel replaced a former "Catastrophic Sexual Transmutation Theory" of the same author (Iltis 1983). Several important character changes can be explained well by this theory. In this connection, evidence is presented that initially the interest of prehistoric people may have been directed to teosinte as a source of sugar from the sweet pith and as a vegetable. Domestication for the grain began only when mutated fruitcases made the kernels more easily accessible (Iltis 2000). The competing third theory that a complicated series of single gene mutations should have been accumulated cannot explain the explosive evolution of maize which began about the time of teosinte's first appearence in the archeological record. Recently, former theories about a hybrid origin of maize (Harshberger 1893, Schiemann 1932) were re-substantiated by the results of new crossing experiments. Backcrosses and F2 populations of a hybrid of Zea diploperennis with a primitive maize contained annual teosintes as well as maize plants having typical characters of the modern maize (Mangelsdorf 1986). Recent crossing of Tripsacum dactyloides with Zea diploperennis gave fertile but perennial offspring that have larger ears and larger kernels than the earliest known samples of primitive domesticated maize but the identical chromosome number 2n=20 like modern maize (Eubanks 1995). The direction of maize domestication was strongly influenced by man's artificial selection for a single stem and large, easily hand-harvested cobs. Without doubt, teosintes and Tripsacum played a major role in the evolution of modern maize as a genetically complex species. Microfossil evidence underline that maize has been taken across the equator to South America already by 5.000 years BC where a secondary centre of diversity developed in Peru. Maize was already the main cereal in the Americas in 1492 and has been quickly distributed over the warmer parts of the Old World. Early in the 16th cent. it was cultivated at the Iberian Peninsula and Italy, and has been taken by the Portuguese to SE Asia and Africa. It was reported from other European countries in mid-16th cent. and apparently reached the E Mediterranean already at that time. From there it moved to Central Europe ("Turkish corn") where it became a commercial crop only in 18th cent. Indications for the presence of maize in Asia before Columbus are strongly under question.

Références

- Alcaraz José, 1949. Maíz. Su cultivo, origen, fiestas, leyendas y literatura ; maíz híbrido. México, Indivisa Manent.

- Anderson E. & Cutler H. C., 1942. Races of Zea Mays : I. Their recognition and classification. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard., 29 : 69-89.

- Bahuchet Serge & Philippson Gérard, 1998. Les plantes d'origine américaine en Afrique bantoue : une approche linguistique. in Chastanet Monique (dir.), Plantes et paysages d'Afrique. Une histoire à explorer. Paris, Karthala ; Centre de recherches africaines. pp. 87-116.

- Bernal D. Mesa, 1957. Historia natural del maíz. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 10 : 13-106. [Important, Spanish texts from XVIth and XVIIth. quoted by Hémardinquer, 1964.

- Bird Robert McK., 1984. South American maize in Central America ? in Stone Doris (ed.), Pre-Columbian plant migration. Cambridge (Massachusetts), Harvard Univ. Press. pp. 39-65.

- Bonafous Matthieu, 1836. Histoire naturelle agricole et économique du maïs. Paris, Huzard. Reprint 1996, Luxembourg, Connaissance et Mémoires Européennes. X-181 p.

- Bonavia Duccio & Grobman Alexander, 1989. Andean maize : its origin and domestication. in Harris D.R. et Hillman G.C. (eds), Foraging and farming. pp. 456-470.

- Brandes Stanley, 1992. Maize as a culinary mystery. Ethnology, 33 (3) : 331-336.

- Brown et Anderson, 1947. [description of maize rces in North-East United-States (Northern Flint), quoted by Finan.

- Brunel, Sylvie, 2012. Géographie amoureuse du maïs. Paris, JC Lattès. 250 p.

- Burland Cottie, 1976. The Aztecs. Gods and fave (sic) in ancient Mexico. NewYork, Galahad Books. (Echoes of the ancient World).

- Carraretto Maryse, 2005. Histoires de maïs. D'une divinité amérindienne à ses avatars transgéniques. Paris, Editions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. 267 p.

- Cauderon André, 1980. Génétique, sélection et expansion du maïs en France depuis trente ans. Cultivar, spécial Maïs, nov. 80: 13-19. [Good account of an important page in French agricultural history.]

- Chauvet, Michel, 2018. Encyclopédie des plantes alimentaires. Paris, Belin. 880 p. (p. 316)

- Cloarec-Heiss France et Nougayrol Pierre, 1998. Des noms et des routes : la diffusion des plantes américaines en Afrique centrale (RCA-Tchad). in Chastanet Monique (dir.) Plantes et paysages d'Afrique. Une histoire à explorer. Paris, Karthala ; Centre de recherches africaines. pp. 117-163.

- Delgado A., 1962. Le maïs dans la culture préhispanique. Actes de Mexico, 40.

- Desjardins, Anne E. & McCarthy, Susan A., 2008. Milho, makka and yu mai: early journeys of Zea mays in Asia. USDA, National Agricultural Library. on line. Synthèse très détaillée avec nombreuses références.

- Doebley John, Goodman Major M. et Stuber Charles W., 1984. Isoenzymatic variation in Zea (Gramineae). Syst. Bot., 9 : 203-218.

- Doebley John F. et Iltis Hugh H., 1980. Taxonomy of Zea (Gramineae). I. A subgeneric classification with key to taxa. Amer. J. Bot. 67 (6): 982-993.

- Doebley John, Wendel Jonathan D., Smith J.S.C., Stuber Charles W. et Goodman Major M., 1988. The origin of Cornbelt maize : the isozyme evidence. Econ. Bot., 42 (1) : 120-131.

- Duchesne, Edouard Adolphe, 1833. Traité du maïs ou blé de Turquie. 366 p. [not seen]

- Dunn Mary Eubanks, 1975. Ceramic evidence for the prehistoric distribution of maize in Mexico. American Antiquity, 40: 305-314.

- Dunn Mary Eubanks, 1977. Prehistoric races of maize and cultural diffusion. Chapel Hill, Dep. of Anthropology. PhD Thesis.

- Ecomusée de la Bresse bourguignonne, 1998. Le maïs, de l'or en épi. Pierre-de-Bresse. 39 p.

- Eyre-Walker Adam, Gaut Rebecca L., Hilton Holly, Feldman Dawn L. & Gaut Brandon S., 1998. Investigation of the bottleneck leading to the domestication of maize. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 95 : 4441-4446.

- FAO, 1993. Le maïs dans la nutrition humaine. Rome, FAO, 174 p. (Collection FAO Alimentation et nutrition, 25).

- Fedoroff Nina, 1984. Les éléments génétiques transposables du maïs. Pour la Science, août 1984 : 24-36.

- Finan John J., 1948. Maize in the great Herbals. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard., 35 : 149-183.

- Franconie Hélène, 1998a. Maïs. Carte onomasiologique et de motivation. Commentaire XXXIII. in Atlas Linguarum Europae (ALE). Roma, Istituto Poligrafico. Vol. I - Commentaires. Fasc. 5 : 45-97.

- Franconie Hélène, 1998b. Les noms du maïs dans les dialectes avant l'arrivée des hybrides. in Le maïs, de l'or en épi. Ecomusée de la Bresse bourguignonne, Pierre-de-Bresse. pp. 34-39.

- Frêche Georges, 1974. Toulouse et la région Midi-Pyrénées au siècle des Lumières. Vers 1670-1789. Paris, Cujas. XVIII-983 p. "Les travaux de Georges Frêche ont sérieusement assis la chronologie" de la diffusion du maïs en Midi-Pyrénées (Ponsot, 2005).

- Fussell Betty, 1992. The story of corn. New-York, Alfred A. Knopf. 358 p.

- Galinat Walton C., 1965. The evolution of corn and culture in North America. Econ. Bot., 19 (4) : 350-357.

- Galinat Walton C., 1992. Maize : gift from America’s first peoples. in Foster Nelson et Cordell Linda S., Chilies to chocolate. Food the Americas gave the world. Tucson, Univ. of Arizona Press. pp 47-60.

- Galinat Walton C. et Lin Bor-Yaw, 1988. Baby corn : production in Taiwan and future outlook for production in the United States. Econ. Bot., 42 (1) : 132-134. (Notes on economic plants).

- Gallais A. (coord.), 1984. Physiologie du maïs (Colloque de Royan, 15-17 mars 1983). Paris, INRA. 574 p.

- García Mouton, Pilar, 2018. Los nombres españoles del maíz. Anuario de Letras. Lingüística y Filología (México), 6 (1) : 121-146.

- Gay J.P., 1984. Fabuleux maïs. Histoire et avenir d'une plante. Pau, Assoc. Gén. des Producteurs de Maïs. 296 p., ill. coul. [Many illustrations, but not enough critical.]

- Grenand, Pierre ; Moretti, Christian ; Jacquemin, Henri & Prévost, Marie-Françoise, 2004. Pharmacopées traditionnelles en Guyane. Créoles, Wayãpi, Palikur. 2e édition revue et complétée. Paris, IRD. 816 p. (1ère éd.: 1987). Voir sur Pl@ntUse.*Harrington John P., 1945. Origin of the word "maize". Wash. Acad. Sci. J., 35 : 68.

- Harshberger J.W., 1893. Maize, a botanical and economic study. Contrib. Bot. Lab. Univ. Pennsylvania, 1: 75-202. [many Indian names].

- Hatt Gudmund, 1951. Mother-corn in America and Indonesia. Anthropos, 16.

- Hémardinquer Jean-Jacques, 1964. Turcicum frumentum : une survivance du principe d'autorité. Candollea, 19 : 221-228.

- Hémardinquer Jean-Jacques, 1966. L'introduction du maïs et de la culture des sorghos dans l'ancienne France. Bull. philologique et historique du CTHS : 429-459.

- Hémardinquer Jean-Jacques, 1973. Les débuts du maïs en Méditerranée (premier aperçu). Mélanges en l'honneur de Fernand Braudel. Toulouse, Edouard Privat. pp. 227-233.

- Hémardinquer Jean-Jacques, 1974. L'introduction du maïs et ses conséquences pendant les invasions françaises en Franche-Comté. Bull. philologique et historique du CTHS : 129-146.

- Hernández Xolocotzi E., 1985. Maize and the greater Southwest. Econ. Bot., 39 : 416-430.

- Iltis Hugh H., 2000. Homeotic sexual translocations and the origin of maize (Zea mays, Poaceae) : a new look at an old problem. Econ. Bot., 54(1) : 7-42.

- Iltis Hugh H. & Doebley John F., 1980. Taxonomy of Zea (Gramineae). II. Subspecific categories in the Zea mays complex and a generic synopsis. Amer. Jour. Bot. 67 (6): 994-1004.

- Johannessen Carl L. & Parker Anne Z., 1989. Maize ears sculptured in 12th and 13th Century A.D. India as indicators of pre-columbian diffusion. Econ. Bot., 43 (2) : 164-180.

- Kalm P., 1974. Description of maize corn as planted and cultivated in North America, and the various uses of this grain. Econ. Bot., 28: 107-113. pub. origin. 1748.

- Katz Esther, 1995. Les fourmis, le maïs et la pluie. J. Agric. Trad. Bot. Appl., 37 : 119-132.

- Katz Solomon H., Hediger M. & Valleroy L., 1974. Traditional maize processing techniques in the New World : anthropological and nutritional significance. Science, 184 : 765-773.

- Katz Solomon H., Hediger M. & Valleroy L., 1975. The anthropological and nutritional significance of traditional maize processing techniques in the New World. in E. Watts, B. Lasker, F. Johnson (eds), Biosocial interrelations in population adaptation. La Haye, Mouton, pp. 195-234.

- Kupzow A. J., 1967-68. Histoire du maïs. J. Agric. Trad. Bot. Appl., 14 : 526-561 ; 15 : 42-88.

- Macneish R.S., 1971. Speculation about how and why food production and village life developed in the Tehuacan valley, Mexico. Archaeology, 24 : 307-315. [teosinte as a vegetable].

- Mangelsdorf, Paul C., 1974. Corn ; its origin, evolution and improvement. Cambridge, Harvard Univ. Press. 262 p. [excellent.]

- Mangelsdorf, Paul C. & Reeves, R.G., 1939. The origin of Indian corn and its relatives. Texas, College Station, 315 p.

- Meade J., 1948. Iziz Centli (El Maíz) : orígenes y mitología. Mexico, Talleres Gráficos de la Nación. [Illustrations from codices and monuments)

- Mesa-Bernal Daniel, 1957. Historia natural del maíz. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Bogotá, 10 (39): 13-106.

- Miles S.W., 1960. Mam residence and the maize myth. in Diamond S. (ed.), Culture in history, New-York, Columbia Univ. Press.

- Moritz L.A., 1955. ‘Corn’. The Classical Quarterly, New Series, 5 (= vol. 49) : 135-141.

- Myrick Herbert, 1903. The book of corn. New-York, Orange Judd Co.

- Nicholson G. Edward, 1960. Chicha maize types and chicha manufacture in Peru. Econ. Bot., 14 : 290-299.

- OECD, 2003. Consensus document on the biology of Zea mays subsp. mays (Maize). Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 49 p. (Series on Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology, 27).

- Parmentier, Antoine Augustin, 1785. Mémoire... sur cette question : Quel seroit le meilleur procédé pour conserver, le plus long-temps possible, ou en grains ou en farine, le Maïs ou Blé de Turquie, plus connu dans la Guienne sous le nom de Blé d’Espagne ? Et quels seroient les différens moyens d’en tirer parti, dans les années abondantes, indépendamment des usages connus et ordinaires dans cette Province ? Augmenté par l’auteur, de tout ce qui regarde l’Historie Naturelle et la culture de ce grain. Bordeaux, A.-A. Pallandre. 164 p. Reprint 1984, Pau, AGPM.

- Petrich Perla, 1985. La alimentación mochó : acto y palabra. Centro de Investigaciones Indígenas, Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas, Chiapas, México.

- Petrich Perla, 1985. Taxonomías culinarias del maíz entre los mochó. Revista de la UNACH, Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, México. (Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas).

- Piperno, Dolores R., 2011. The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments. Current Anthropology, 52 (S4): 453–S470. doi:10.1086/659998

- Piperno, Dolores R. & Flannery, K.V., 2001. The earliest archaeological maize (Zea mays L.) from highland Mexico: new accelerator mass spectrometry dates and their implications. PNAS, 98 (4) : 2101–2103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.2101

- Ponsot Pierre, 2003. Les Bressans, premiers cultivateurs du maïs en France ? in Ponsot Pierre (ed.), La Bresse, les Bresses, de la Préhistoire à nos jours, t. II, Saint-Just (Ain), éd. A. Bonavitacola, pp. 191-204. critical identification of the "grain de Turquie" of Olivier de Serres.

- Ponsot Pierre, 2005. Les débuts du maïs en Bresse sous Henri IV. Une découverte, un mystère. Histoire et sociétés rurales, 23 : 117-136.

- Portères Roland, 1955. L’introduction du maïs en Afrique. J. Agric. Trad. Bot. Appl., 2 : 221-231. carte.

- Portères Roland, 1967. Premières iconographies européennes du maïs (Zea mays L.). J. Agric. Trad. Bot. Appl., 14 : 500-501.

- Rakoto-Ratsimamanga, Albert ; Boiteau, Pierre & Mouton, Marcel, 1969. Eléments de pharmacopée malagasy. tome & (Notices 1 à 39). Tananarive, Société pour la promotion de la pharmacopée malagasy. 306 p. Voir sur Pl@ntUse (amidon)

- Rong-Lin Wang, Stec Adrian, Hey Jody, Lukens Lewis & Doebley John, 1999. The limits of selection during maize domestication. Nature, 398 : 236-239.

- Schilperoord, Peer, 2017. Plantes cultivées en Suisse – Le maïs. 40 p. DOI: 10.22014/978-3-9524176-5-2.1

- Version allemande : Kulturpflanzen in der Schweiz – Mais. DOI: 10.22014/978-3-9524176-4-5.1

- Schumann Otto, 1988. El origen del maíz (versión k’ekchi’). in La etnología : temas y tendencias. Coloquio Kirchhoff. México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas - UNAM : 213-218.

- Slocum M., 1965. The origin of corn and other tzeltal myths. Tlalocan, 5 (1).

- Smith Andrew, 1997. The pop-corn polka : or how maize popped into the American mainstream. Petits Propos Culinaires, 56 : 16-22.

- Stoianovich Traian, 1966. Le maïs dans les Balkans. Annales. Economie, sociétés, civilisations : 1027-29. (at least)

- Sturtevant E. Lewis, 1899. Varieties of corn. USDA, Exper. Station Bull. 57.

- Tapley, W. T.; Enzie, W. D. & van Eseltine, G. P., 1934. The vegetables of New-York, Vol. 1, Part III, Sweet corn. N.Y. Agric. Exp. Sta., Geneva. (Sweet corn, p. 329-471 du pdf)

- TRAMIL, Pharmacopée végétale caribéenne, éd. scient. L. Germosén-Robineau. 2014. 3e éd. Santo Domingo, Canopé de Guadeloupe. 420 p. Voir sur Pl@ntUse

- Valladares L., 1957. El hombre y el maíz. México, Costa-Amic.

- Weatherwax Paul, 1954. Indian corn in old America. New-York, Macmillan Co. 253 p.

- Wellhausen E.J., Roberts L.M. & Hernández Xolocotzi E., in collaboration with P.C. Mangelsdorf, 1951. Razas de maíz en México. México, Secretaría de Agricultura y Ganadería. (Folleto técnico 5).

- Wellhausen E.J., Roberts L.M. & Hernández Xolocotzi E., in collaboration with P.C. Mangelsdorf, 1951. Races of maize in Mexico. Bussey Inst., Harvard Univ.

- Wilkes Garrison, 1966. Teosinte: the closest relative of maize. Cambridge (Massachussets), Bussey Institution of Harvard Univ.

- Wilkes Garrison, 1977. The origin of corn. Studies of the last hundred years. In Seigler David (ed.). Crop resources. New-York, Academic Press, pp. 211-223.

- Wilkes Garrison, 1979. Mexico and Central America as a centre for the origin of agriculture and the evolution of maize corn. Crop Improv., 6 : 1-18.

- Wilkes Garrison, 1989. Maize : domestication, racial evolution and spread. in Harris D.R. & Hillman G.C. (eds), Foraging and farming. pp. 440-455.

Liens

- BHL

- FAO Ecocrop

- Feedipedia

- Grieve's herbal : plante et styles

- GRIN

- Iowa State (agronomy)

- IPNI

- Mansfeld

- Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany

- Mots de l'agronomie :

- Gallais, André, Le maïs, de la téosinte aux variétés hybrides

- Duret, Claude (1605), Le maïs dans l’Histoire admirable des plantes et herbes esmerveillables et miraculeuses en nature...

- Vouette, Isabelle, Le maïs en France avant les hybrides

- Haudricourt & Hédin, 1943, Les substitutions de plantes cultivées : le cas du maïs

- Multilingual Plant Name Database

- NewCrop Purdue

- Plant List

- Plants for a future

- Plants of the World Online

- PROSEA sur Pl@ntUse

- PROTA sur Pl@ntUse

- TAXREF

- Tela Botanica

- USDA Crops (economy)

- Useful Tropical Plants Database

- Wikipédia

- Wikiphyto

- World Flora Online