Ipomoea batatas (TRAMIL)

| |

= Batatas edulis (Thunb.) Choisy

- Nom accepté : Ipomoea batatas

- Voir sur la TRAMILothèque (davantage d’illustrations)

Sommaire

Noms vernaculaires significatifs TRAMIL

- République Dominicaine : batata

- noms créoles : patate douce, patate

Distribution géographique

Régions tropicales et tempérées.

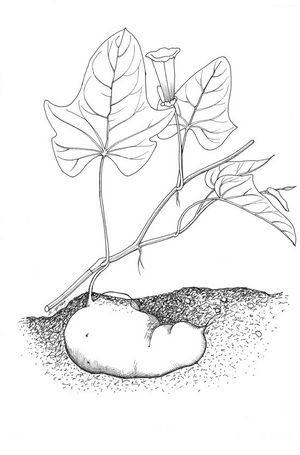

Description botanique

Plante grimpante vivace à racine tubéreuse comestible. Tige succulente mais parfois fine et herbacée, glabre ou pubescente, ramifiée. Feuilles de cordées à ovées, entières, dentées ou profondément lobées, de 5 à 10 cm de long, glabres ou rarement pubescentes, à pointe aiguë à acuminée, mucronées. Inflorescences cymeuses à cymeuses-ombelliformes avec peu de fleurs; fleurs avec sépales oblongs; corolle campanulée avec limbe de couleur lavande à pourpre-lavande et gorge plus sombre, blanche dans certaines variétés. Capsule ovoïde, glabre, brun clair à jaune paille, biloculaire, à 4 valves; graines 4, glabre brun foncé à brun.

Voucher : Jiménez,131,JBSD

Emplois traditionnels significatifs TRAMIL

- brûlure superficielle : tubercule, naturel, en application locale1

Recommandations

Selon l’information disponible :

L’emploi contre les brûlures superficielles est classé REC basé sur l’usage significatif traditionnel documenté par les enquêtes TRAMIL et l’information scientifique publiée. En cas de détérioration du patient ou que les symptômes de la brûlure persistent pendant plus de 7 jours, consulter un médecin.

Limiter l’emploi traditionnel à des brûlures superficielles (lésion épidermique) peu étendues (moins de 10% de la surface corporelle) et localisées en dehors des zones à haut risque telles que le visage, les mains, les pieds et les parties génitales. Employer la préparation exclusivement en application locale.

Toute application topique doit obéir à de strictes mesures d’hygiène pour empêcher la contamination ou une infection surajoutée.

Ne pas administrer pendant la grossesse, en période d’allaitement ni à des enfants de moins de 8 ans.

Chimie

Le tubercule contient des sesquiterpènes : acide abscissique2-3, 6-hydroxy-dendrolasine, 6-oxo-dendrolasine, 9-hydroxy-farnésol, 9-oxo-farnésol4, ipoméamarone5-6, 4-hydroxy-myoporone6-7; coumarines : aesculétine8, phénylpropanoïdes : acide caféique8-9, acides chlorogénique, iso-chlorogénique, néo-chlorogénique9; flavonoïdes : caféoyl-p-hydroxy-benzoyle-cyanidine-3-diglucoside-5-glucoside et autres dérivés glucoside, rubrobrasicine10; stéroïdes : campestérol, β-sitostérol, estigmastérol11, daucostérol12; caroténoïdes : β-β-5,6-5’, 6’,6-tétrahydro-carotène13 (5R,6S,5’R,6’S)-lutéochrome, (5R,6S,5’R,8’R)- lutéochrome14; alcaloïdes : acide indole-3-acétique3, 6-(3-méthyl- 2-butényl-amino)-9-β-d-glucopyranoside purine15, cis-riboside zéatine16, monoterpènes : linalol-β-glucoside, nérol-β-glucoside17; lipides : subérine18, α-β-glucoside-terpinéol17; protéines : adp-glucose-amidon-glucosyltransférase19.

Activités biologiques

L’extrait éthanolique de la plante entière, du bulbe et de la feuille (ces derniers séparément), in vitro, a été actif contre Mycobacterium leprae, M. phlei, M. fortuitum, Neisseria ovis, N. caviae, Branhamella catarrhalis, Moraxella osloensis, Bacillus megaterium, B. brevis et Candida albicans20.

L’extrait éthanolique (95%) du tubercule, administré par voie sous cutanée chez la souris femelle, n’a pas montré d’effet estrogénique21.

L’extrait aqueux lyophilisé du tubercule (2 mg/mL), in vitro, n’a montré aucune activité immunostimulante sur les macrophages22.

L’extrait aqueux de tubercule frais (100 μL/mL) n’a montré aucune activité anti-allergénique contre les cellules LEUK-RBL 2H323.

L’extrait méthanolique de l’écorce de tubercule lavé et séché, et l’écorce utilisée comme un pansement, (150-200 g) a été appliqué en gel au rat Wistar, modèle de cicatrisation de plaies par excision et incision, avec mesure de la résistance à la traction de la peau, le temps d’épithélialisation, la contraction de la plaie, la teneur en hydroxyproline de la croûte, l’acide ascorbique et le malondialdéhyde plasmatique. Une puissante activité de cicatrisation a été enregistrée, qui peut être due à un mécanisme antioxydant subjacent24.

Toxicité

Le bulbe de la plante est comestible, mais quand il est infesté par le champignon Ceratostomella fimbriata il devient toxique pour l’homme, même à faible dose, provoquant dyspnée, anorexie et vomissements25. L’extrait méthanolique de peau lavée et séchée du tubercule (jusqu’à 2 g/kg) par voie topique au rat Wistar (180-200 g) des deux sexes, n’a pas provoqué de signes de toxicité24.

Les parties aériennes sont utilisées comme nourriture pour les rats des deux sexes26.

On ne dispose pas d’information garantissant l’innocuité de son emploi médicinal sur des enfants, des femmes enceintes ou allaitantes.

Préparation et dosage

Le tubercule d’Ipomoea batatas constitue un aliment de consommation humaine relativement étendue.

Contre les brûlures superficielles :

Laver et peler la patate douce crue, appliquer la pelure du côté de l’amidon en cataplasme sur la zone affectée. Couvrir avec une compresse ou un linge propre et changer toutes les 12 heures.

Toute préparation médicinale doit être conservée au froid et utilisée dans les 24 heures.

Références

- GERMOSEN-ROBINEAU L, GERONIMO M, AMPARO C, 1984 Encuesta TRAMIL. enda-caribe, Santo Domingo, Rep. Dominicana.

- NAKATANI M, KOMEICHI M, 1991 Distribution of endogenous zeatin riboside and abscisic acid in tuberous roots of sweet potato. Nippon Sakumotsu Gakkai Kiji 60(2):322-323.

- NAKATANI M, KOMEICHI M, 1991 Chantes in the endogenous level of zeatin riboside, abscisic acid and indole acetic acid during formation and thickening of tuberous roots in sweet potato. Nippon Sakumotsu Gakkai Kiji 60(1):91-100.

- BURKA L, FELICE L, JACKSON S, 1981 6-oxodendrolasin, 6-hydroxydendrolasin, 9-oxofarnesol and 9-hedroxyfarnesol, stress metabolites of the sweet potato. Phytochemistry 20:647-652.

- WOOD G, HUANG A, 1975 The detection and quantitative determination of ipomeamarone in damaged sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas). J Agr Food Chem 23(2):239-241.

- BURKA L, KUHNERT L, 1977 Biosynthesis of furanosesquiterpenoid stress metabolites in sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas) oxidation of ipomeamarone to 4-hydroxymyoporone. Phytochemistry 16(12):2022-2023.

- BURKA L, KUHNERT L, WILSON B, HARRIS T, 1974 4-hydroxymyoporone, a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of pulmonary toxins produced by Fusarium solani infected sweet potatoes. Tetrahedron Lett 15(46):4017-4020.

- MINAMIKAWA T, AKAZAWA T, URITANI I, 1962 Isolation of esculetin from sweet potato roots with black rot. Nature(London) 195:726-727.

- SONDHEIMER E, 1958 On the distribution of caffeic acid and the chlorogenic acid isomers in plants. Arch Biochem Biophy 74(1):131-138.

- MIYAZAKI T, TSUZUKI W, SUZUKI T, 1991 Composition and structure of anthocyanins in the periderm and flesh of sweet potatoes. Engei Gakkai Zasshi 60(1):217-224.

- OSAGIE AU, 1977 Phytosterols in some tropical tubers. J Agr Food Chem 25(5):1222-1223.

- MATLACK MB, 1935 A phytosterol and phytosterolin from the sweet potato. Science 81:536.

- DE ALMEIDA LB, PENTEADO M, BRITTON G, UEBELHART P, ACEMOGLU M, EUGSTER C, 1988 Isolation and absolute configuration of beta, beta-carotene diepoxide. Helv Chim Acta 71(1):31-32.

- DE ALMEIDA LB, PENTEADO M, SIMPSON K, BRITTON G, ACEMOGLU M, EUGSTER C, 1986 Isolation and characterisation of (5R,6S,5’R,8’R)-and (5R,6S,5’R,8’S)- luteochrome from Brazilian sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas Lam.). Helv Chim Acta 69(7):1554-1558.

- HASHIZUME T, SUYE S, SOEDA T, SUGIYAMA T, 1982 Isolation and characterization of a new glucopyranosyl derivative of 6-(3-methyl-2-butenylamino) purine from sweet potato tubers. Febs Lett 144(1):25-28.

- HASHIZUME T, SUYE S, SUGIYAMA T, 1981 Occurrence and level of cis-zeatin riboside in sweet potato tubers (Ipomoea batatas L). Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 10:131-134.

- OHTA T, OMORI T, SHIMOJO H, HASHIMOTO K, SAMUTA T, OHBA T, 1991 Identification of monoterpene alcohol beta-glucosides in sweet potatoes and purification of a shiro-koji beta-glucosidase. Agr Biol Chem 55(7):1811-1816.

- KOLATTUKUDY P, KRONMAN K, POULOSE A, 1975 Determination of structure and composition of suberin from the roots of carrot, parsnip, rutabaga, turnip, red beet and sweet potato by combined gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectr. Plant Physiol 55(3):567-573.

- DOWNTON WJ, HAWKER JS, 1975 Evidence for lipid-enzyme interaction in starch synthesis in chillingsensitive plants. Phytochemistry 14:1259-1263.

- LE GRAND A, 1985 Les phytothérapies anti-infectieuses (partie 3 : Une Evaluation) Amsterdam, Pays-Bas.

- WALKER BS, JANNEY JC, 1930 Estrogenic substances. II. An analysis of plant sources. Endocrinology 14(6):389-392.

- MIWA M, KONG Z, SHINOHARA K, WATANABE M, 1990 Macropohage stimulating activity of foods. Agr Biol Chem 54(7):1863- 1866.

- TANAKA Y, KATAOKA M, KONISHI Y, NISHMUNE T, TAKAGAKI Y, 1992 Effects of vegetable foods on beta-hexosaminidase release from rat basophilic leukemia cells (RBL-2H3). Jpn J Toxicol Environ Health 38(5):418-424.

- VANDANA PANDA V, SONKAMBLE M, PATIL S, 2011 Wound healing activity of Ipomoea batatas tubers (sweet potato). Functional Foods in Health and Disease 10:403-415.

- AGUILAR CONTRERAS A, ZOLLA C, 1982 Plantas Tóxicas de México. División de información etnobotánica. Ciudad, México: Unidad de investigación biomédica en medicina tradicional y herbolaria del Instituto Mexicano del seguro social. p118- 120.

- ORTALIZA IC, DEL ROSARIO IF, CAEDO MM, ALCARAZ AP, 1969 The availability of carotene in some Philippine vegetables. Philippine J Sci 98(2):123-131.