Entandrophragma cylindricum (PROTA)

Introduction |

| General importance | |

| Geographic coverage Africa | |

| Geographic coverage World | |

| Medicinal | |

| Timber | |

| Fuel | |

| Ornamental | |

| Forage / feed | |

| Conservation status | |

Entandrophragma cylindricum (Sprague) Sprague

- Protologue: Bull. Misc. Inform. Kew 1910: 180 (1910).

- Family: Meliaceae

- Chromosome number: 2n = 36, 72

Vernacular names

- Sapelli mahogany, sapele mahogany, West African cedar, scented mahogany (En).

- Sapelli, cédrat d’Afrique (Fr).

- Sapelli (Po).

Origin and geographic distribution

Entandrophragma cylindricum is widespread, occurring from Sierra Leone east to Uganda, and south to DR Congo and Cabinda (Angola).

Uses

The wood, usually traded as ‘sapelli’, ‘sapele’, ‘aboudikro’ or ‘assié’, is highly valued for flooring, interior joinery, interior trim, panelling, stairs, furniture, cabinet work, musical instruments, carvings, ship building, veneer and plywood. It is suitable for construction, vehicle bodies, toys, novelties, boxes, crates and turnery. The bole is traditionally used for dug-out canoes. Wood that can not be valorized as timber is used as firewood and for charcoal production.

In Central Africa the bark is used in traditional medicine. Bark decoctions or macerations are taken to treat bronchitis, lung complaints, colds, oedema and as anodyne, whereas bark pulp is applied externally to furuncles and wounds. Bark extracts have been used as protectant of stored maize. The tree is planted as roadside tree and ornamental shade tree. Caterpillars of the butterfly Imbrasia oyemensis are commonly found on the leaves; they are edible and in East Africa much sought after for human consumption.

Production and international trade

Sapelli is one of the most important export timbers of tropical Africa. During the 1960s the main exporters were Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. In 1963–1974 average annual exports from Côte d’Ivoire were 122,000 m³ of logs and 15,700 m³ of sawn wood. Average annual exports from Ghana in 1963–1967 were 48,000 m³ of logs and 39,000 m³ of sawn wood. In 1969–1970 Cameroon annually exported about 52,000 m³ of logs per year, and Nigeria, Congo and the Central African Republic together about 60,000 m³ per year.

Nowadays the wood is mainly harvested in Central Africa, with an export value of at least US$ 165 million in 2003, with exports mainly from Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Congo. The Central African Republic exported 41,000 m³ of Entandrophragma cylindricum logs in 2003, at an average price of US$ 391/m³, and 29,000 m³ of sawn wood, at an average price of US$ 473/m³. Congo exported 211,000 m³ of logs in 2003, at an average price of US$ 224/m³, 221,000 m³ in 2004, at US$ 219/m³, and 150,000 m³ in 2005, at US$ 194/m³. Cameroon exported 108,000 m³ of sawn sapelli wood in 2003, at an average price of US$ 806/m³, 120,000 m³ in 2005 at US$ 350/m³, and 89,000 m³ in 2006, at US$ 422/m³. In 2004 the export of veneer was 3000 m³ from Ghana at an average price of US$ 870/m³ and 9000 m³ from Congo at an average price of US$ 334/m³. Smaller amounts of plywood were exported from Ghana (1000 m³ in 2004) and the Central African Republic, at an average price of US$ 347/m³ and US$ 372/m³, respectively.

Properties

The heartwood is pinkish brown when freshly cut, darkening upon exposure to reddish brown or purplish brown, and distinctly demarcated from the creamy white to pinkish grey, up to 10 cm wide sapwood. The grain is interlocked or wavy, texture fairly fine. Quarter-sawn surfaces are regularly striped or have a roe figure. The wood has a distinct cedar-like smell.

The wood is medium-weight, with a density of 560–750 kg/m³ at 12% moisture content. It air dries fairly rapidly, but is liable to warping and distortion. Quarter-sawing before drying and careful stacking are recommended. Mild schedules are needed for kiln drying. The rates of shrinkage are medium to moderately high, from green to oven dry 3.5–7.6% radial and 4.3–9.8% tangential. Once dry, the wood is moderately stable in service.

At 12% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is (66–) 95–184 N/mm², modulus of elasticity 8900–13,800 N/mm², compression parallel to grain 40–75 N/mm², compression perpendicular to grain about 8 N/mm², shear 7–18 N/mm², cleavage 15–20 N/mm, Janka side hardness 4180–6730 N and Janka end hardness 5650–7450 N.

The wood saws and works easily with both hand and machine tools; it has only slight blunting effects on cutting edges. In planing and moulding operations, a 15–20° cutting angle is recommended to avoid picking up of grain. Finishing gives usually good results, with a nice polish. The wood is not liable to splitting in nailing and screwing, with good holding properties. The gluing, staining and polishing properties are good, but the steam bending properties are poor. The wood is suitable for the production of both sliced and rotary veneer; steaming for 48–72 hours at 85°C gives good results. It is moderately durable, being liable to powder-post beetle, pinhole borer and marine borer attacks and with moderate resistance to termites. The heartwood is resistant to preservatives, and the sapwood is moderately resistant.

The lactone entandrophragmin has been isolated from the heartwood and bark. It showed high toxicity to tadpoles. The bark also contains several acyclic triterpenoids, called sapelenins. Bark extracts showed inhibitory effects on the reproduction of the maize weevil Sitophilus zeamais. The tannin present in the bark has been used experimentally to produce tannin-formaldehyde resin, which can be used as lacquer, although the drying time was rather long, 5–7 hours.

The essential oil from the bark has been analyzed for trees originating from Cameroon and the Central African Republic. The major constituents were γ-cadinene (9–23%), α-copaene (7–22%) and T-cadinol (18–28%). The seeds contain about 45% oil. The fatty acid composition of the oil is characterized by the presence of about 50% cis-vaccenic acid, a rare isomer of oleic acid, that can be used in the industrial production of nylon-11. Other major fatty acids are stearic acid (16%), oleic acid (7%), linoleic acid (5%) and linolenic acid (6%).

Adulterations and substitutes

The wood of Entandrophragma candollei Harms, often traded as ‘kosipo’, resembles that of Entandrophragma cylindricum, but is less highly valued because it is slightly denser and less nicely coloured and figured.

Description

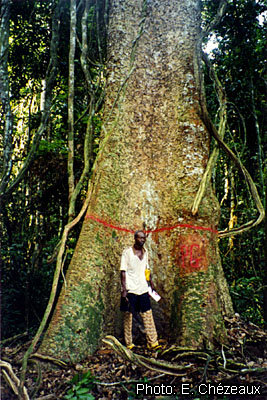

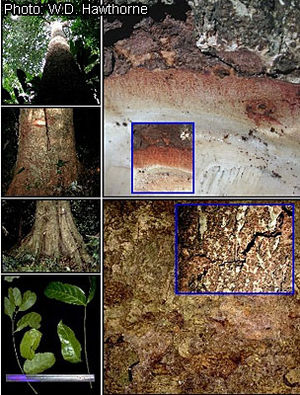

- Deciduous, dioecious large tree up to 55(–65) m tall; bole branchless for up to 40 m, straight and cylindrical, up to 200(–280) cm in diameter, with low, blunt buttresses up to 2 m high, rarely up to 4 m; bark surface silvery grey to greyish brown or yellowish brown, becoming irregularly scaly with scales leaving shallow pits with numerous lenticels, inner bark pinkish, soon becoming brown upon exposure, fibrous, with a strong cedar-like smell; crown rounded; young twigs brownish short-hairy, marked with lenticels.

- Leaves alternate, clustered near ends of twigs, paripinnately compound with 10–19 leaflets; stipules absent; petiole 5–13 cm long, flattened or slightly channelled, often slightly winged at base, rachis 7–17 cm long; petiolules 1–6 mm long; leaflets opposite to alternate, oblong-elliptical to oblong-lanceolate or oblong-ovate, 4–15 cm × 2–5 cm, cuneate to rounded and slightly asymmetrical at base, usually short-acuminate at apex, papery to thinly leathery, almost glabrous, pinnately veined with 6–12 pairs of lateral veins.

- Inflorescence an axillary or terminal panicle up to 25 cm long, short-hairy.

- Flowers unisexual, regular, 5-merous; pedicel 1–2.5 mm long; calyx cup-shaped, lobed to about the middle, 0.5–1 mm long, sparsely short-hairy outside; petals free, ovate, 3–4 mm long, sparsely short-hairy outside, greenish white; stamens fused into an urn-shaped tube c. 2 mm long, with 10 anthers at the slightly toothed apex; disk cushion-shaped, with 20 indistinct ridges; ovary superior, conical, 5-celled, style very short, stigma disk-shaped, with 5 lobes; male flowers with rudimentary ovary, female flowers with smaller, non-dehiscing anthers.

- Fruit a pendulous, cylindrical capsule 6–14(–22) cm × 2.5–4 cm, brown to purplish black, dehiscing from the apex and base with 5 woody valves, up to 20-seeded with seeds attached to the upper part of the central column.

- Seeds 6–11 cm long including the large apical wing, pale brown.

- Seedling with epigeal germination, but cotyledons often remaining within the testa; hypocotyl 2–4 cm long, epicotyl 6–9 cm long; first 2 leaves opposite, simple.

Other botanical information

Entandrophragma comprises about 10 species and is confined to tropical Africa. It belongs to the tribe Swietenieae and is related to Lovoa, Khaya and Pseudocedrela.

Anatomy

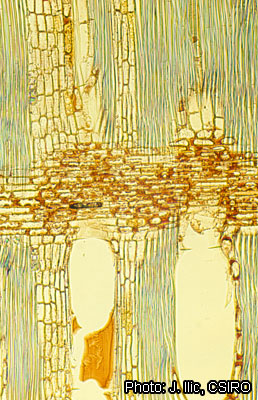

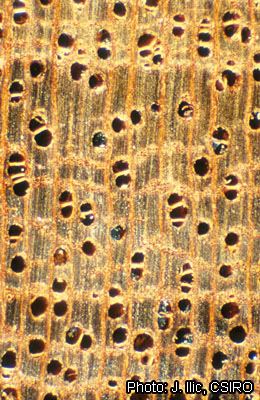

Wood-anatomical description (IAWA hardwood codes):

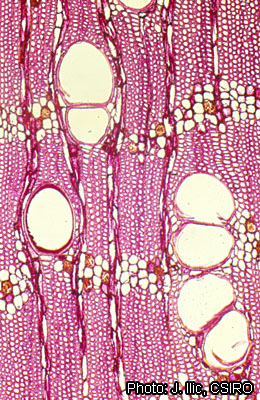

- Growth rings: (1: growth ring boundaries distinct); (2: growth ring boundaries indistinct or absent).

- Vessels: 5: wood diffuse-porous; 13: simple perforation plates; 22: intervessel pits alternate; 23?: shape of alternate pits polygonal; 24: intervessel pits minute (≤ 4 μm); 25: intervessel pits small (4–7 μm); 30: vessel-ray pits with distinct borders; similar to intervessel pits in size and shape throughout the ray cell; 42: mean tangential diameter of vessel lumina 100–200 μm; 47: 5–20 vessels per square millimetre; 58: gums and other deposits in heartwood vessels.

- Tracheids and fibres: 61: fibres with simple to minutely bordered pits; (65: septate fibres present); 66: non-septate fibres present; 69: fibres thin- to thick-walled.

- Axial parenchyma: 78: axial parenchyma scanty paratracheal; 79: axial parenchyma vasicentric; 80: axial parenchyma aliform; (81: axial parenchyma lozenge-aliform); (82: axial parenchyma winged-aliform); 83: axial parenchyma confluent; 85: axial parenchyma bands more than three cells wide; (86: axial parenchyma in narrow bands or lines up to three cells wide); 89: axial parenchyma in marginal or in seemingly marginal bands; 92: four (3–4) cells per parenchyma strand; 93: eight (5–8) cells per parenchyma strand.

- Rays: (97: ray width 1–3 cells); (98: larger rays commonly 4- to 10-seriate); (104: all ray cells procumbent); 106: body ray cells procumbent with one row of upright and/or square marginal cells; 115: 4–12 rays per mm.

- Storied structure: (118: all rays storied); 122: rays and/or axial elements irregularly storied.

- Secretory elements and cambial variants: 131: intercellular canals of traumatic origin.

- Mineral inclusions: 136: prismatic crystals present; 137: prismatic crystals in upright and/or square ray cells; 141: prismatic crystals in non-chambered axial parenchyma cells; (142: prismatic crystals in chambered axial parenchyma cells).

Growth and development

Under natural conditions, seeds germinate abundantly, but mortality of seedlings is high, less than 1% reaching 10 cm stem diameter. Seedlings grow slowly, 20–40 cm/year. Root development takes considerable time. Seedlings up to 2 years old require light shade, but thereafter they should be gradually exposed to more light. They can survive for several years in the shade without significant growth, but when a gap is created in the forest providing enough light further development into a tree starts. The mean annual diameter increment for trees in the Central African Republic has been established at 3.9 mm, but the variability is large. For trees planted in lines in forest in Cameroon, the average annual height growth during 40 years was 30–50 cm and average annual diameter growth 4–8 mm. Trees planted in the open in Côte d’Ivoire reached an average height of 5.4 m and an average stem diameter of 10 cm after 7 years, with a survival rate of 74%.

Trees start flowering when 35–45 years old. Fruit production starts when trees have reached bole diameters above 50 cm. This has implications for forest management; minimum felling diameters should be well above 50 cm to allow natural regeneration. Research in Cameroon suggests that a reduction in the number of trees capable of producing seeds is the main limiting factor for regeneration after logging, rather than limits to pollen dispersal; there seems to be extensive pollen flow over larger distances. Trees can become over 500 years old.

Entandrophragma cylindricum trees lose their leaves for 0.5–1 month, or gradually change leaves during 2–3 months. In Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire trees are deciduous for a short period in October–November; flowering occurs near the middle of the dry season, in February–March. In the Central African Republic the trees change leaves from November to January. Mature fruits develop about 5 months after flowering. Fruits usually open on the tree and the seeds are dispersed by wind, although most seeds seem to fall close to the mother tree. Seed production is erratic. Although flowering may be common, fruit production is often irregular, e.g. 90% of trees with bole diameters above 50 cm flower each year in Cameroon, but only 50% of them develop fruits. In the Central African Republic 79% of the observed trees with bole diameter over 50 cm flowered in a 2 year period, and 76% fruited.

Ecology

Entandrophragma cylindricum is most common in semi-deciduous forest, particularly in regions with an annual rainfall of about 1750 mm, a dry period of 2–4 months and a mean annual temperature of 24–26°C. It tolerates dry forest better than other Entandrophragma spp. However, it can also be found in evergreen forest. In Uganda it occurs in rainforest at 1100–1500 m altitude, sometimes in thickets and gallery forest. It prefers well-drained localities.

Entandrophragma cylindricum is characterized as a non-pioneer light demander, although it was indicated as exceptionally shade-tolerant after studies in DR Congo. Natural regeneration is often scarce in natural forest, but logging operations creating gaps may promote regeneration, larger gaps appearing more favourable. Natural regeneration in gaps created by selective logging in forest in Nigeria and Congo was very poor. Regeneration in forest in the Central African Republic 18 years after logging was inadequate, whereas a study in DR Congo showed that secondary forest resulting from the abandonment of slash-and-burn agriculture offers favourable conditions for regeneration.

Propagation and planting

The 1000-seed weight is about 330 g. Fresh seeds may have a high germination rate, 80–95%. However, seeds lose their viability rapidly, often within 3 weeks. Germination starts 14–26 days after sowing. Soaking of the seeds for one night is reported to speed up germination. Overhead shade is required for young seedlings. The seedlings perform poorly under full light conditions. Seeds can be stored for some time in sealed containers in a cool place, but insect damage, to which they are very susceptible, should be avoided, e.g. by adding ash. Cuttings 90–110 cm long have been used successfully for propagation.

Management

Forests in the Central African Republic may contain 7 Entandrophragma cylindricum stems above 10 cm diameter per ha and a wood volume of 25 m³/ha. In southern Cameroon the average density is up to one tree of more than 60 cm bole diameter per ha, and the average wood volume is up to 11.5 m³/ha. In Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon timber plantations of Entandrophragma cylindricum have been established, but only at a very small scale, with less than 10 ha and 425 ha, respectively. Line planting in the forest is practised in Cameroon.

Diseases and pests

Hypsipyla robusta shoot borers may severely attack young trees, often in their second or third year and when grown in full sunlight. Attacked stems often show poor growth and form. Hypsipyla robusta may also infest seeds. Several lepidopterous insects attack the leaves, fruits and seeds.

Harvesting

In Ghana the minimum felling diameter for boles of Entandrophragma cylindricum has been fixed at 110 cm, in Cameroon at 100 cm, in Liberia at 90 cm, in Central African Republic, Gabon and Congo at 80 cm, and in Côte d’Ivoire at 60 cm.

Yield

In the beginning of the 1990s in forests in Congo Entandrophragma cylindricum was selectively logged together with Entandrophragma utile (Dawe & Sprague) Sprague and Triplochiton scleroxylon K.Schum. in a rotation of 30–40 years and removing 1–2 trees/ha, with a wood volume of 10–15 m³.

Handling after harvest

Most freshly harvested logs float in water and can thus be transported by river. A test in Cameroon showed that 2% of the logs had sunken after 14 months in water. Common log defects which should be taken into consideration during processing are ring and cup shakes.

Genetic resources

Entandrophragma cylindricum is the most common Entandrophragma species in much of its distribution area. In 1973 the total exploitable timber volume in Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, the Central African Republic and Congo together has been estimated at over 50 million m³. However, the commercial interest in the valuable timber has resulted in extraction of large individuals from the forest in many regions. It is included in the IUCN Red list as vulnerable.

In Cameroon the genetic diversity of populations in logged-over forest and non-disturbed forest was established by characterization of microsatellite loci. The populations showed the same high level of genetic diversity and a low genetic differentiation, indicating that genetic diversity is within rather than among populations.

Prospects

Entandrophragma cylindricum provides one of the commercially most important timbers of Africa in terms of quantities produced as well as in terms of wood quality. This has resulted in heavy pressure on the populations, and in many regions Entandrophragma cylindricum is still not exploited on a sustainable basis. The low growth rates under natural conditions, the long time needed to reach maturity in terms of fruit production and poor dispersal ability of the seed seem to be serious drawbacks. It has been suggested that intensive silviculture, possibly involving the use of shifting cultivation in a taungya-like system, is needed to achieve sustainable management. Entandrophragma cylindricum does not seem to be a logical choice for planting in agroforestry systems because it grows too slowly.

Major references

- Bolza, E. & Keating, W.G., 1972. African timbers: the properties, uses and characteristics of 700 species. Division of Building Research, CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia. 710 pp.

- Burkill, H.M., 1997. The useful plants of West Tropical Africa. 2nd Edition. Volume 4, Families M–R. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 969 pp.

- CAB International, 2005. Forestry Compendium. Entandrophragma cylindricum. [Internet] http://www.cabicompendium.org/fc/datasheet.asp?CCODE=ENT1CY. April 2008.

- CTFT (Centre Technique Forestier Tropical), 1974. Sapelli. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 154: 27–40.

- Garcia, F., Noyer, J.L., Risterucci, A.M. & Chevallier, M.H., 2004. Genotyping of mature trees of Entandrophragma cylindricum with microsatellites. Journal of Heredity 95(5): 454–457.

- Katende, A.B., Birnie, A. & Tengnäs, B., 1995. Useful trees and shrubs for Uganda: identification, propagation and management for agricultural and pastoral communities. Technical Handbook 10. Regional Soil Conservation Unit, Nairobi, Kenya. 710 pp.

- Palla, F., Louppe, D. & Forni, E., 2002. Sapelli. Forafri, Libreville, Gabon & Cirad-Forêt, Montpellier, France. 4 pp.

- Styles, B.T. & White, F., 1991. Meliaceae. In: Polhill, R.M. (Editor). Flora of Tropical East Africa. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands. 68 pp.

- Takahashi, A., 1978. Compilation of data on the mechanical properties of foreign woods (part 3) Africa. Shimane University, Matsue, Japan, 248 pp.

- Voorhoeve, A.G., 1979. Liberian high forest trees. A systematic botanical study of the 75 most important or frequent high forest trees, with reference to numerous related species. Agricultural Research Reports 652, 2nd Impression. Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen, Netherlands. 416 pp.

Other references

- Agyei-Nimoh, S., 2003. Preparation of lacquer from tannin extracted from the bark of sapele (Entandrophragma cylindricum) species. B.Sc. Chemistry thesis, Department of Chemistry, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. 44 pp.

- ATIBT (Association Technique Internationale des Bois Tropicaux), 1986. Tropical timber atlas: Part 1 – Africa. ATIBT, Paris, France. 208 pp.

- CIRAD Forestry Department, 2003. Sapelli. [Internet] Tropix 5.0. http://tropix.cirad.fr/africa/sapelli.pdf. April 2008.

- de Saint-Aubin, G., 1963. La forêt du Gabon. Publication No 21 du Centre Technique Forestier Tropical, Nogent-sur-Marne, France. 208 pp.

- Durand, P.Y., 1978. Propriétés physiques et mécaniques des bois de Côte d’Ivoire: moyennes d’espèce et variabilité intraspécifique. Centre Technique Forestier Tropical, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. 70 pp.

- Durrieu de Madron, L., Dipapoundji, B. & Lugard, G.R., 2003. Fructification du sapelli par classe de diamètre en forêt naturelle en Centrafrique. Canopée 23: 23–24.

- Farmer, R.H., 1972. Handbook of hardwoods. 2nd Edition. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, United Kingdom. 243 pp.

- Hall, J.S., Medjibe, V., Berlyn, G.P. & Ashton, P.M.S., 2003. Seedling growth of three co-occurring Entandrophragma species (Meliaceae) under simulated light environments: implications for forest management in central Africa. Forest Ecology and Management 179(1/3): 135–144.

- Hawthorne, W. & Jongkind, C., 2006. Woody plants of western African forests: a guide to the forest trees, shrubs and lianes from Senegal to Ghana. Kew Publishing, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, United Kingdom. 1023 pp.

- InsideWood, undated. [Internet] http://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/search/. May 2007.

- Kleiman, R. & Payne-Wahl, K.L., 1984. Fatty acid composition of seed oils of the Meliaceae, including one genus rich in cis-vaccenic acid. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 61(12): 1836–1838.

- Lourmas, M., Kjellberg, F., Dessard, H., Joly, H.I. & Chevallier, M.H., 2007. Reduced density due to logging and its consequences on mating system and pollen flow in the African mahogany Entandrophragma cylindricum. Heredity 99(2): 151–160.

- Makana, J.R., 2004. Fellowship report: How to improve the regeneration of African mahoganies in the northeastern block of the Democratic Republic of Congo. ITTO Tropical Forest Update 14(4): 20–21.

- Neuwinger, H.D., 2000. African traditional medicine: a dictionary of plant use and applications. Medpharm Scientific, Stuttgart, Germany. 589 pp.

- Normand, D. & Paquis, J., 1976. Manuel d’identification des bois commerciaux. Tome 2. Afrique guinéo-congolaise. Centre Technique Forestier Tropical, Nogent-sur-Marne, France. 335 pp.

- Oteng-Amoako, A.A. (Editor), 2006. 100 tropical African timber trees from Ghana: tree description and wood identification with notes on distribution, ecology, silviculture, ethnobotany and wood uses. 304 pp.

- Parant, B., Boyer, F., Chichignoud, M. & Curie, P., 2008. Présentation graphique des caractères technologiques des principaux bois tropicaux. Tome 1. Bois d’Afrique. Réédition. CIRAD-Fôret, Montpellier, France. 186 pp.

- Siepel, A., Poorter, L. & Hawthorne, W.D., 2004. Ecological profiles of large timber species. In: Poorter, L., Bongers, F., Kouamé, F.N. & Hawthorne, W.D. (Editors). Biodiversity of West African forests. An ecological atlas of woody plant species. CABI Publishing, CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 391–445.

- Tailfer, Y., 1989. La forêt dense d’Afrique centrale. Identification pratique des principaux arbres. Tome 2. CTA, Wageningen, Pays Bas. pp. 465–1271.

- Vivien, J. & Faure, J.J., 1985. Arbres des forêts denses d’Afrique Centrale. Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique, Paris, France. 565 pp.

- Zollo, P.H.A., Ndoye, C., Koudou, J., Menut, C., Lamaty, G. & Bessière, J.M., 1999. Aromatic plants of tropical Central Africa IV: Chemical composition of bark essential oils of Entandrophragma cylindricum Sprague growing in Cameroon and in Central African Republic. Journal of Essential Oil Research 11(2): 173–175.

Sources of illustration

- Styles, B.T. & White, F., 1991. Meliaceae. In: Polhill, R.M. (Editor). Flora of Tropical East Africa. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands. 68 pp.

- Wilks, C. & Issembé, Y., 2000. Les arbres de la Guinée Equatoriale: Guide pratique d’identification: région continentale. Projet CUREF, Bata, Guinée Equatoriale. 546 pp.

Author(s)

- V.A. Kémeuzé, Millennium Ecologic Museum, BP 8038, Yaoundé, Cameroon

Correct citation of this article

Kémeuzé, V.A., 2008. Entandrophragma cylindricum (Sprague) Sprague. In: Louppe, D., Oteng-Amoako, A.A. & Brink, M. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 17 December 2024.

- See the Prota4U database.