Copal (Stross)

- See the main page Copal (in French)

This paper was published in U-Mut Maya, 1997. 6:177-186.

Copied from WaybackMachine. The copyright remains to the author. This article is reproduced here due to its great interest.

Contents

- 1 ABSTRACT

- 2 INTRODUCTION

- 3 COPAL AS DEITY FOOD

- 4 COPAL AS MEDICINE, GLUE, AND SOUL ATTRACTANT

- 5 COPAL IN DIVINATION AND OTHER RITUAL CONTEXTS

- 6 RITUAL CENSING OF SACRED OBJECTS

- 7 THE VARIETY OF COPAL BEARING TREES

- 8 COPAL AND TRANCE

- 9 COPAL AS ENCAUSTIC BINDER

- 10 CONCLUSION

- 11 NOTES

- 12 REFERENCES CITED

- 13 FIGURES

- 14 PLANT SPECIES REFERENCED IN TEXT

ABSTRACT

Tree resins utilized as incense and known throughout Mesoamerica as copal have diverse plant sources. Studies of these resins, how people use them, and what they think about them, are poorly represented in the literatures of ethnobotany and anthropology. Moreover, confusion lingers concerning which Mesoamericans use copal from which trees for what purposes. These copal resins have many uses besides incense — from medicine to glue — as illustrated here with a sampling from ethnographic reports that demonstrate also some of copal's ambiguity of reference in Mesoamerica. The illustrations are selected to also support the contention here made that Mesoamerican Indians now and in the past have seen a symbolic connection between maize and copal, most notably connected with copal's use as food for the gods, and evidenced also in the modeling of maize ears from it, lake offerings of maize shaped and blue-green painted lumps of copal, and manufacture of miniature tortilla shaped incense disks wrapped like tamales. Evidence is offered here of copal use as a binder for cinnabar painted on jade and also for color pigments on encaustic murals, hitherto believed to be frescoes. In addition a hypothesis is offered with preliminary supporting evidence that copal smoke may have been employed for trance induction by shamans. Finally infrared spectrometry on several samples of copal from various parts of Mesoamerica suggests that the prototypical copal resin used in much of Mesoamerica was from the tree species Bursera bipinnata.

INTRODUCTION

Copal is aromatic tree resin employed in Mesoamerica as incense. The word comes, by way of Spanish, from Aztec Nahuatl copalli, and due to regional differences in naming and usage several different trees and their resins bear the name copal. Some of the resins called copal have other uses besides that of burning as incense[1]. For example, copal has been variously used for chewing, glueing, bringing rain, and purifying meat; it has also been used as a pigment binder, as a varnishing agent, and as medicine for several different ailments.

In addition to regional variation concerning which plant species are utilized as copal and to what other uses copal is put, there is confusion in the literature as to identification of the trees involved — even when they are identified botanically, which they often are not. The confusion is compounded by name changes that reflect advances made in botanical systematics. Current ongoing studies using microscopy, infrared spectrometry and gas chromotography / mass spectrometry promise to distinguish kinds and components of copal and thus to disentangle some of the confusion about which plants are the source of what resin (e.g. Langenheim 1969 ; Castorena, Garza-Valdes and Stross 1993). It is hoped that detailed descriptive ethnography and ethnobotanical work can soon improve the precision with which we identify plants used as copal incense by which communities in Mesoamerica. Despite the quantity of information still lacking for Mesoamerica about plant resins in general, and copal resin in particular, a few studies touching on copal in Mesoamerica have been published (e.g. Langenheim and Balser 1975 ; Beck 1970 ; Balser 1960), and a preliminary outline of copal uses and tree species identifications in Mesoamerica is possible. Moreover we can here formulate and furnish support for some new suggestions about copal resin use and symbolism at this time. Consonant with these goals, one intent of this paper is to stimulate further and more systematic investigation of this intriguing category of copal plants and their resin products by showing some of the varieties of copal use in Mesoamerica.

COPAL AS DEITY FOOD

Buried within studies on Mesoamerican Indian societies are observations on copal collection, manufacture, and use, along with information about the social context of its use. Among other things, many of these observations can be interpreted to indicate that indigenous Mesoamerican societies saw a close relationship between maize and copal, maize being primarily a food for humans, and copal — the "blood" of trees — being primarily a food for deities. Its main employ was as incense offerings to the deities.

As incense, copal resin is even today sprinkled on live coals held in braziers, from which dense black clouds of aromatic smoke resembling dark storm clouds rise up as offerings to deities. Among the northern Lacandón Maya of lowland Chiapas in southern Mexico:

- the most common offering is copal incense (pom), which is made from the resin of the pitch pine (Pinus pseudostrobus). Young boys are given the task of gathering the sap from the pine trees, which is collected by making shallow diagonal cuts in the trunk. The sap flows along the path of the cut and drips into a leaf cup placed at the base of the tree. The resin is then pounded into a thick paste and stored in large gourd bowls in the god house...Pom is important because it is the principal foodstuff given to the gods Although obviously not edible by humans, the Lacandón believe that when pom burns, the incense transforms into tortillas, which the gods consume (McGee 1990: 44).[2]

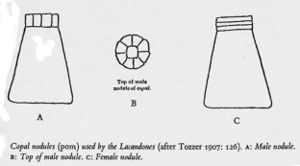

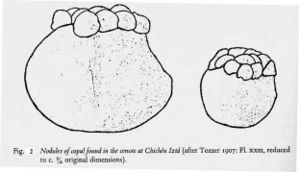

The Lacandón also fashion truncated cones, shaped rather like maize ears, made of copal, as part of a drinking ceremony, with eight smaller bits of the resin — like kernels of maize — surrounding a central one atop a "male" cone, and three disks of copal resin — like tortillas — atop a "female" cone (Figure 1). The male cones are similar to prehispanic copal nodule offerings found in the cenote at Chichén Itzá (Figure 2), as well as to a cone of copal retrieved from a lake in the Nevado de Toluca in central Mexico (Figure 3). The resin bits and disks differentiating male and female copal cones recall the nodular and disk forms in which copal is sold elsewhere in the Maya region today.

The copal offerings from the sacred well at Chichén Itzá were painted greenish blue (Lounsbury 1971: 109), and in some of them were embedded pieces of worked green jade such as beads and discs (Coggins and Schane 1984: 130-1). Painting copal the color of jade recalls the fact that jade placed in the corpse's mouth in Maya burials has been interpreted as symbolizing maize as food for the soul of the newly departed (Coe 1988: 225), while copal itself is said to be food of the gods.

Other evidence relating copal to maize as food can be found among the Chortí Mayans, living in eastern Guatemala. During the harvest they model four ears of maize from copal resin taken from the bark of a species of Bursera, to be deposited in the granary as protection for the newly harvested maize against harmful spirits (Wisdom 1940: 403). This practice is not unlike what Yucatec Maya farmers must be doing when they mold and place little wax figures (box kib) in the four corners of the milpa to protect it. They bleed themselves, by pricking their fingers, to feed and animate these box kib protectors (private communication by Michael Carrasco).

Frequently copal in Guatemala is sold in disc form as wafers wrapped in banana leaf or maize husk packages. The tortilla shaped wafers are approximately the size and shape of some of the Classic Maya jade discs, and there is likely to be a symbolic relationship between these two different forms of metaphorical "food".

The Mam Maya of highland Guatemala maintain a ritual cycle called pomixi 'copal of maize' that has been well described (Wagley 1957), and part of which consists of dripping sacrificial blood on copal that is then used to cense seed maize before planting. Smoking seed maize with copal is commonly found in other Mesoamerican communities, as well, and constitutes another important symbolic link between maize and copal. According to the Ixil Mayans of highland Guatemala, miniature "tortillas" of copal wrapped in corn husks are seen as food for the gods (Figure 4). "Though the gods do not eat as mortals do, they must imbibe the products of human ritual, primarily the smoke of incense" (Colby and Colby 1981: 42). Whereas the Lacandón consider pom — the usual Mayan name for copal, which is itself a borrowing from Mixe-Zoquean — to be "tortillas" of the gods, Zinacantan Tzotzil Mayans living in the central highlands of Chiapas say that white wax candles are the deities' "tortillas" (Vogt 1969:403), but they make offerings of burning incense to the gods as well, placing chips of copal wood or sprinkling nodules of copal resin on a censer bearing burning embers. Two types of copal (Tzotzil pom) are distinguished by the Zinacantecos; "genuine incense" derived from Bursera excelsa or Bursera tomentosa trees (Laughlin 1975: 282), and "mud incense" derived from Bursera bipinnata (Figure 5). Resin from these trees is also used to plug tooth cavities and to fix loose teeth (Vogt 1969: 394-5).

COPAL AS MEDICINE, GLUE, AND SOUL ATTRACTANT

Another species of the same genus, Bursera simaruba (the gumbolimbo tree), is a Zinacanteco remedy for loose teeth and dysentery but is not used by Tzotzil speakers for incense, although some other Mayans use it so. The Chortí plant a tree as a symbolic cross in preparation for the pilgrimage to Esquipulas. The tree is identified as Bursera simaruba, and it stands at the center rear of the altar area, just as do conventional crosses in other ceremonies (Wisdom 1950: 476 ; Fought 1972: 525). Huastec Mayans living in San Luis Potosí, more than 500 miles away from the Tzotzil, and even farther from the Chortí, also utilize Bursera simaruba for purposes other than incense, such as in the treatment of burns, headache, nosebleed, fever, and stomach ache, and for predicting rain by its flowering (Alcorn 1984: 569).

Huastec (Teenek) copal for censing comes from the Protium copal. Also known as Elaphrium copal, Protium copal is a close relative of Bursera, and both are of the family Burseraceae. In addition to being the standard incense burned for most Huastec Mayan ritual offerings, and for censing the four directions, nodules of this copal are counted out into the corners during the house renewal ceremony and at the new year, recalling the protective function of modeled copal in Chortí granaries[3]. It is also employed as a remedy for stomach pain, fright, and dizziness (Alcorn 1984:763).

The copal of the Guatemalan Chortí Mayans that is used for censing is called uhtz'ubte' in Chortí and copal, copal de santo, or palo de santo in Spanish. It has been identified as resin from a species of Bursera.

- The gum [resin] is boiled, shaped into hard pellets, burned with live coals in incense burners, and the fumes allowed to pass over the body to cure various illnesses, to protect oneself against sorcery, sickness, and misfortune, and to cleanse the body after contact with the ritually unclean, especially sick persons and corpses. A tea of the bark is taken to relieve dysentery. A type of sandal is carved from the wood, to be worn on muddy trails. The wax [resin] is burned in the houses to drive away insects and when freshly made serves as an all-purpose solder or glue. This is used to mend leaks in all non-cooking containers, to plug the mouth end of flutes, to tip drum sticks, to glue wood, especially in the manufacture of the TUN drum, fiddles, and guitars, and for glueing the leather straps to tool handles. It is burned in incense burners at nearly all the religious ceremonies, and the Catholic churches of the area are said to use it exclusively (Wisdom 1950: 929-930)

The Chortí also use copal to initiate and to conclude a successful deer hunt, censing the deer's carcass with copal fumes to purify the meat. "The incense is said to drive out evil spirits from the dead body" (Wisdom 1940: 73). "Before the hunter sets out he must have a dream, in which the deer-god informs him of the price he must pay for the animal. He is told that he must pay a certain number of "pesos" of copal gum... The hunter prepares his copal pesos and burns them at midnight before his altar, offering them to both the saints and the deer-god" (Wisdom 1940: 72).

The Sierra Popoluca, a Zoquean group living on the north end of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, use copal smoke in connection with hunting also. The jawbones of deer obtained in the hunt are saved and smoked with copal in order to allow the souls of these animals to return to their spirit home in the charge of the Master of Animals (Foster 1945: l86). Mixe is a language in the same Mixe-Zoquean family to which Sierra Popoluca belongs, and Mixe speakers inhabit the Mexican state of Oaxaca where it joins the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The copal most commonly used by the Totontepec Mixe for smoke offerings of incense is identified as Bursera jorullensis (Schoenhals 1965: 344).

Information on the more than half a million Quiché Mayans of highland Guatemala, living in a number of different communities, is uneven in quantity and quality, but it is possible to say that within this language group can be found several different kinds of copal incense, and even in a given community more than one type is likely to be recognized. The types may be differentiated by quality, cost, and sometimes in terms of varying appropriateness for particular occasions, as related in the following passage.

- Pom, a resinous tree gum... The darkest kind, wrapped in two pieces of pumpkin shell... is now used only in Momostenango for the most sacred rites. The second variety, wrapped in cornhusks, serves for other ceremonies. The kind sold currently in small gray pebbles in all the markets is used extensively in Indian huts as a disinfectant or insecticide and as an incense before the household altars. Poor people burn it in church (de Jongh Osborne 1975: 114n)

Among the Quiché today pine resin copal is as common as any kind. Dennis Tedlock, who did fieldwork in Momostenango, writes of another kind of copal that is "the resin from the bark of the palo jiote tree (Hymenaea verrucosa)" (1985:332). Ordinarily in Mesoamerica the palo jiote is a species of Bursera (e.g. B. simaruba or B. bipinnata or B. excelsa), so possibly the tree referred to is actually a Bursera. Edmonson identifies the pom (copal) referred to in the Quiché sacred book written down during early Colonial times, the Popol Vuh, as "incense wafers or discs 1 1/2" in diameter, sold in banana-fiber packages 15" long containing two dozen pieces and made from various trees (Icica sp. [now Protium], Elaphrium sp. [now Bursera], Protium copally)" (1965: 90).

COPAL IN DIVINATION AND OTHER RITUAL CONTEXTS

In the southern Huasteca region, among Nahuatl speakers copal incense smoke is used in two ways for divination. In some areas patterns in the smoke of burning incense are interpreted by the shaman, constituting one of the many forms of divination found in Mesoamerica (Sandstrom 1991: 235). In other areas "the shaman picks up fourteen grains of corn and holds them in incense smoke. He then chants, asking the sacred hill spirits to guide him. Next, he casts the grains [of censed maize] onto the cloth and interprets where they fall" (Sandstrom 1991: 236). In Mitla, Oaxaca, the Zapotecs burn copal in water so as to diagnose the cause of a fright. The copal's underside is supposed to provide a picture of the fright's cause (Parsons 1936: 120).

In the southern Huasteca, as elsewhere in Mesoamerica, ritual censing with copal never occurs in a contextual vacuum. In the Nahuatl village of Amatlán For example,

- Villagers call rituals xochitlalia (sing. "flower earth," literally "to put down flowers") in Nahuatl and costumbres ("customs") when speaking Spanish... Rituals themselves are colorful and filled with action. They often run continuously for several days at a time, producing in participants a dreamlike state of semiexhaustion. Most people consume quantities of potent cane alcohol that adds to the otherworldly quality of these events. Rituals are accompanied by lilting, repetitive guitar and violin music called xochisones, a Nahuatl-Spanish term meaning "flower sounds"... In larger events, lines of dancers perform in ornate headdresses while shaking gourd rattles. Shamans and their helpers construct elaborate altars decorated with greenery and flowers and load them with offerings and rows of lighted beeswax candles. One or more copal incense braziers pour out billows of resinous, aromatic smoke as the shaman sacrifices chickens or turkeys and dances wildly holding bundles of cut paper figures (Sandstrom 1991: 279-280).

The ritual context in which copal is burned, and the consistency with which similar elements are found throughout Mesoamerica underscores the integral position that copal enjoys within the ritual structure.

RITUAL CENSING OF SACRED OBJECTS

Mesoamerican Indian communities use incense on nearly every ritual occasion, and in addition to the burning of copal per se, specific items are ritually censed on appropriate occasions. These items, in addition to the seed maize mentioned above, are particularly sacred, and include such things as saints images and their clothes, altars, crosses, and community banners. This censing or smoking of sacred objects is a practice that was present when the Spaniards arrived, and evidence from jade artifacts of pre-Columbian times can confirm its anterior occurrence.

Unburnt copal resin probably deriving from Bursera bipinnata has also been found on jade and other greenstone artifacts of Classic Maya times. A translucent green jasper pectoral from the Ahaw Collection, for example, has yielded traces of copal according to fluorescence analysis of yellowish spots seen on the greatly magnified artifact surface (Garza-Valdes 1991: 348), and the pectoral itself possesses the characteristic odor of copal (Figure 6). The traces of unburned copal attest to copal's probable use by Classic Maya as a binder for application of the cinnabar commonly applied to the surface of jade artifacts, traces of which were found on the pectoral in question (Stross 1992).

THE VARIETY OF COPAL BEARING TREES

Most copal incense in Mesoamerica is traceable to several species in the family Burseraceae, usually of the genus Bursera, and secondarily to a smaller number of species of the genus Pinus in the family Pinaceae. Additionally the genus Hymenaea of the family Leguminosae has been said to be represented among the bearers of incense resin, and the Tarahumara and Tepehuan of northwest Mexico are known to employ Coutaria pterosperma (called clusia or copalquín) of the family Rubiaceae in this capacity (Pennington 1969: 345).

In the Maya region of southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, resin from Bursera bipinnata (also known as Elaphrium bipinnatum) is among the most frequently employed of the copal incenses today and apparently also in former times, and two important uses attributed to resin from this particular species, but not discussed in the literature, remain to be discussed here; (1) for induction of a trance state in the shaman, and (2) as a paint binder in Mesoamerican murals that have long been wrongly called frescoes.

COPAL AND TRANCE

It is well known that shamans in the Americas, both Latin America and North America, use the smoke of tobacco to enter the trance state (Wilbert 1987), and referring specifically to current practice in Asia, another anthropologist states that "a widespread technique for engendering trance is the inhalation of juniper smoke" (Kalweit 1987: 78). In Bali, incense smoke used to be inhaled for the induction of trance as part of an "ancient trance ritual" involving dance. Dr. Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, M.D. has proposed that copal smoke was employed in Mesoamerica by the Classic Maya, among others, to induce a trance state in shamans (private communication). The smoke could be quite effective in a person who has already fasted (as is customary among shamans before important ritual events), who has already practiced entering the trance state, and who might well be assisted in the endeavor by other attention focusing aspects of rituals involving copal smoking as illustrated above. Other information regarding the use of copal, and specifically Bursera bipinnata, lends additional credibility to the suggestion.

Emboden remarks on the fact that the Aztecs of Mexico knew of a tree that they called teuvetli which was:

- incised to release its resins so that they might be used in ritual sacrifice. Slaves and captives had to climb to very high altars on these occasions and force was not appropriate to sacrificial ritual. It was necessary to induce a trance state that would not impair motor coordination and cause them to fall. We know little of this narcosis except that given this control of muscle combined with passive behavior it was most likely a hypnotic. Bursera bipinnata (Elaphrium bipinnatum) seems the most likely candidate for this mysterious tree... Bursera species were used in diverse medical practices among the Aztecs. All of these have resin canals running through the bark and when slashed, a gummy resin is exuded. Leaves frequently spray a mist of volatile oils when broken. These gums and oils were applied directly to induced wounds before the ceremony so that a direct connection with the circulatory system of the blood might be established... In contemporary Mexico some species of Bursera (especially B. penicillata) are used to allay pain in instances of toothache (Emboden 1979: 4).

The connection of Bursera bipinnata to trance induction from putting the resin directly into the bloodstream suggests the possibility that it might well also have been used for trance through inhalation of the smoke. Support for this interpretation comes from Father Jose Luis Guerrero who notes that in the valley of Mexico during the 16th cent, the shaman-priests inhaled smoke from copal to enter the trance state, waving the smoke to the noses from the smoking censor (private communication 1993).

COPAL AS ENCAUSTIC BINDER

The second use mentioned above, also involving Bursera bipinnata, is that of providing a binder for pigment to be applied to a dry surface in the making of murals in Mesoamerica. Samples from murals of Tamuin in northeastern Mexico, and of Bonampak in Chiapas, Mexico, have been analyzed by Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes and found to contain resin from Bursera bipinnata in quantities consistent with its use as a binder. Thus the murals were not frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, but rather they were more like as encaustic murals, utilizing copal as a binder for the pigment (Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes private communication).

CONCLUSION

Evidence has been provided herein supporting the contention that indigenous Mesoamericans perceived copal as food for the gods somehow paralleling the use of maize as food for humans. The symbolism employed in its production and use motivates our connecting maize and copal. Modeled lumps of copal resembling maize ears (even to the maize kernels) used as offerings and as protection for the maize harvest; painted cone shaped offerings of copal a blue green color like jade, which is itself seen as a kind of "food"; and tortilla shaped disks of copal produced for burning as incense constitute evidence for this hypothesis. Even more persuasive is the almost ubiquitously expressed native perception that smoking incense is food offered to the gods, sometimes articulated in terms of smoke being transformed into tortillas.

In addition, some of the variety of uses to which copal resins are put has been documented here, as has been some of the ambiguity of reference for copal in Mesoamerica. The possible use of copal for induction of trance state in Mesoamerican shamans has been suggested, and the use of copal as a binder for pigment in murals at Tamuin and Bonampak noted, requiring a redefinition of these murals not as frescoes, but rather as encaustic murals. Finally, on the basis of infrared spectrometry we have proposed that the prototypical copal resin used in much of Mesoamerica probably was from the Bursera bipinnata tree. Infrared spectral analyses were performed on a copal sample from a Late Preclassic tomb in Apatzingan in Guerrero, Mexico (L.A. Garza Valdes, private communication 1992), on a copal sample taken from a lake in the crater in the volcanic peak Nevado de Toluca, Mexico; on a sample bought in the market in Guatemala City, Guatemala; and on a copal sample used by a Tzeltal shaman in Tenejapa, Chiapas, Mexico. All of these proved to have spectra very similar to that of Bursera bipinnata.

In order to augment the documentation and suggestions presented here, as well as to verify and expand the basis for a systematic classification of copals in Mesoamerica, it is hoped that information provided above will help stimulate collection in Mesoamerica of accurately provenanced copal plant species from contexts in which indigenous groups can specify with some certainty both the native names for the plants (along with any known Spanish equivalents) and the local uses to which the resins are put.

We also need to know the process by which the copal resins are gathered, what times of the year they are gathered, by whom, and where, as well as what rituals if any attend the gathering process. Of course the investigator should take careful notes on how the copal is utilized and of the fullest possible context of its utilization for various purposes. In addition the native perceptions of the meaning and relationships of copal to their culture needs as full a documentation as possible.

NOTES

- acknowledgment. This paper owes much to the ideas of Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes and to his spectrographic studies. Thanks are due Fred Valdez for copal samples.

- ↑ One source of confusion derives from the fact that some economic botanists use the term 'copal resins' to reference a diverse category of "several resins, primarily from the Caesalpinoideae subfamily of the leguminosae, but also from unrelated sources, some fossilized" (Schery 1972: 234), whereas the typical copal resins used as incense in Mesoamerica come from the family Burseraceae and have been termed 'elemi' in the literature (Schery 1972: 242). Other plant secretions gathered in ways similar to producing copal, and employed for ritual burning or for medicinal purposes, have been, but should not be, confused with copal. Such products include: sweetgum, rubber, and chicle. The sweetgum or storax (Spanish copalillo and liquidámbar) is Liquidambar styraciflua L. [Hamamelidaceae]; rubber (Spanish goma and hule) is Castilla elastica Sesse [Moraceae]); chicle (Spanish chicle, chicozapote, and sapodilla) is Manilkara achras (Mill.) Fosberg [Sapotaceae], formerly Achras sapota, Manilkara zapota.

- ↑ The Lacandones, of Lacanhá at least, also use a different kind of tree, not a pine, for incense, and collect the resin from a particular tree that is growing near the ruins of Bonampak (Alfonso Morales, private communication 1993). This tree is probably a Bursera.

- ↑ In the mid 16th Century, Yucatec Maya craftsmen making wooden idols constructed a special hut in which to make them. In this hut they placed copal "at the four points of the compass" so as to burn it for deities called Acantun 'Set-up stone' (Thompson 1970: 191), recalling current practice of Huastec Mayans.

REFERENCES CITED

- Alcorn, Janis. 1984. Huastec Mayan Ethnobotany. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Balser, Carlos 1960. Notes on Resin in Aboriginal Central America, Acta, 34th International Congress of Americanists (Vienna, 1960), pp. 374-380.

- Beck, Curt W. 1970. Amber in Archaeology. Archaeology 23(1): 7-11.

- Castorena, J., L.A. Garza-Valdes, and B. Stross. Archaeological Sample Identified as Copal (Bursera bipinnata) by Capillary Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectometry. (paper/report presented to the Society of American Archaeologists in St. Louis, Missouri, 1993.

- Coe, Michael D. Ideology of the Maya Tomb. in E.P. Benson and G. G. Griffin, eds., Maya Iconography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 222-235.

- Coggins, Clemency and Orrin Shane III. 1984. Cenote of Sacrifice. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Colby, Benjamin N. and Lore M. 1981. The Daykeeper: The Life and Discourse of an Ixil Diviner. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- de Jongh Osborne, Lilly. 1975. Indian Crafts of Guatemala and el Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Edmonson, Munro S. 1965. Quiche-English Dictionary. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute.

- Emboden, William. 1979. Narcotic Plants. New York: Macmillan Pub. Co., Inc.

- Foster, George 1945. Sierra Popoluca Folklore and Beliefs. University of California Publications on American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 42, No. 2.

- Fought, John G. 1972. Chortí (Mayan) Texts I. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Garza-Valdes, Leoncio A. 1991. Technology and weathering of Mesoamerican jades as guides to Authenticity. Materials Research society Symposium Proceedings Volume 185, Materials Issues in Art and archaeology II, P.B. Vandiver, J.R. Druzik and G. Wheeler, (eds.), 321-357.

- Kalweit, Holger. 1987. Shamans, Healers, and Medicine Men. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

- Langenheim, Jean 1969. Amber: A botanical inquiry. Science 163: 1157-1168.

- Langenheim, Jean H. and Carlos A. Balser 1975. Botanical origins of resin objects from aboriginal Costa Rica. Vínculos: Revista de Antropología del Museo Nacional de Costa Rica 12: 72-82.

- Laughlin, Robert M. 1975. The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantan. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Lounsbury, Floyd G. 1971. On the derivation and reading of the 'Ben-Ich' prefix. in E.P. Benson, ed., Mesoamerican Writing Systems. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, pp.99-144.

- McGee, R. Jon. 1990. Life, Ritual, and Religion Among The Lacandon Maya. Belmont: Wadsworth, Inc.

- Parsons, Elsie Clews. 1936. Mitla: Town of the Souls. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pennington, Campbell 1969. The Tepehuan of Chihuahua: Their Material Culture. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Sandstrom, Alan R. 1991. Corn is Our Blood. Norman. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Schoenhals, Alvin and Louise C. 1965. Vocabulario Mixe de Totontepec. Mexico City: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Schery, Robert W. 1972. Plants For Man (second edition). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Stross, Brian. 1992. The heavenly portal carved in green stone. Paper presented at Materials Research Society Meetings, April 30, 1992, San Francisco.

- Tedlock, Dennis. 1985. Popol Vuh. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. 1970. Maya History and Religion. Norman: Univeristy of Oklahoma Press.

- Vogt, Evon Z. 1969. Zinacantan. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

- Wagley, Charles. 1957. Santiago Chimaltenango. Guatemala: Seminario de Integracion Social.

- Wilbert, Johannes. 1987. Tobacco and Shamanism in South America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wisdom, Charles 1940. The Chortí Indians of Guatemala. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wisdom, Charles 1950. Materials on the Chortí Language. Middle American Cultural Anthropology Microfilm Series 5, Item 28. Chicago: University of Chicago Library.

FIGURES

Figure 4 Cornhusk holder for copal disks from highland Guatemala

Figure 5 Spectrum of Bursera bipinnata

Figure 6

- a. Ahaw pectoral (photograph by Leoncio Garza-Valdes)

- b. Photomicrograph of pectoral surface w/ copal stains of Bursera similar to spectrum of B. bipinnata.

PLANT SPECIES REFERENCED IN TEXT

Burseraceae

- Bursera bipinnata (DC.) Engl. [copal]

- Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. [jiote, palo mulato]

- Bursera diversifolia Rose [copal]

- Bursera excelsa (HBK.) Engl. [copal]

- Bursera tomentosa (Jacq.) Tr. & Pl. [copal]

- Bursera jorullensis (DC.) Engl. [copal]. Accepted name : Bursera copallifera

- Bursera penicillata (DC.) Engl. [copal]

- Protium copal (Schlecht. & Cham.; DC) Engl. = Icica copal (Schlecht. & Cham.) [copal]

Leguminosae

- Hymenaea courbaril L. [sausage tree, cuapinol, stinktoe]

- Hymenaea verrucosa

Pinaceae

- Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. [pitchpine, ocote, copal]

Rubiaceae

- Coutaria pterosperma. Coutarea. Accepted name : Hintonia latiflora