Burkea africana (PROTA)

Introduction |

Burkea africana Hook.

- Protologue: Icon. pl. 6: t. 593–594 (1843).

- Family: Caesalpiniaceae (Leguminosae - Caesalpinioideae)

- Chromosome number: 2n = 28

Vernacular names

Burkea, wild syringa, wild seringa, red syringa, sand syringa (En).

Origin and geographic distribution

Burkea africana is widespread, occurring from Senegal east to Sudan and Uganda, and south to Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique and northern South Africa.

Uses

The wood is used for poles (e.g. for heavy construction and fences), parquet flooring, furniture, railway sleepers, utensils such as mortars, tool handles, drums and other musical instruments such as xylophones and balafons. It has been claimed by wagon makers that Burkea africana wood is the best for making hubs because it does not shrink or split. It is suitable for joinery, interior trim, ship building, mine props, sporting goods, toys, novelties, draining boards, carving and turnery. The wood is also used as firewood and for charcoal production, and has been used commonly for iron smelting because of the hot flame and little ash produced.

The bark, roots and leaves are commonly used in traditional medicine. Bark decoctions or infusions are used to treat fever, cough, catarrh, pneumonia, menorrhoea, headache, inflammation of tongue and gums, poisoning and skin diseases. Powdered bark is applied to ulcers and wounds, and to treat scabies. Root decoctions or infusions are used to treat stomach-ache, abscesses, oedema, epilepsy, bloody diarrhoea, gonorrhoea, syphilis and toothache. In Burkina Faso roots have been used as antidote against arrow poison. Leaves are used in the treatment of fever, headache, epilepsy, ascites and conjunctivitis. Twigs are used as chewing sticks. Pounded bark is used as a fish poison.

Young flowers are eaten in sauces. In Burkina Faso leaves are used as condiment. The bark and pods have been used for tanning leather. The bark is used as a dye to make the roots of Combretum zeyheri Sond. grey to blackish; these roots are woven into baskets in Namibia. The gum from the bark is edible; it is locally considered an aphrodisiac. Burkea africana is planted as a roadside tree and ornamental. It is host to caterpillars of Saturnid moths (Cirina forda and Rohaniella pygmaea), which are collected by people as food; after boiling and frying, these are considered a delicacy. The flowers produce nectar collected by honey bees.

Production and international trade

The wood of Burkea africana is mainly used locally and traded in limited volume internationally. Production and trade statistics are not available. Bark and roots are commonly sold on local markets for medicinal purposes.

Properties

The heartwood is brown with grey and green tinges, turning reddish brown or dark brown upon exposure. It is usually distinctly demarcated from the yellowish or pinkish white, c. 2.5 cm wide sapwood. The grain is interlocked or wavy, texture fine to moderately fine and even. The wood is lustrous and displays a nice stripe figure.

The wood is heavy, with a density of 735–1020 kg/m³ at 12% moisture content. It air dries moderately fast, with little tendency to corrugate, split or distort, but kiln drying should be done with great care. It takes about 3 weeks to kiln dry boards of 2.5 cm thick. The rates of shrinkage are moderate, from green to oven dry 2.9–5.6% radial and 4.2–9.2% tangential. Once dry, the wood is stable in service.

At 12% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is 84–143 N/mm², modulus of elasticity 12,940 N/mm², compression parallel to grain 48–85 N/mm², compression perpendicular to grain 12 N/mm², shear 14.5–15 N/mm², Janka side hardness 6490 N and Janka end hardness 7605 N.

Although the wood is hard, it is not difficult to saw, but it is difficult to work with hand tools. The wood is susceptible to tearing in planing operations due to the presence of interlocked grain. It takes a nice polish upon finishing. Pre-boring in nailing is recommended because the wood is liable to splitting. The gluing properties are good. The wood turns well. It is durable, but the sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus attack. Extracts of the heartwood showed fungicidal and termiticidal properties, and this in combination with the strongly hydrophobic character of the wood and the high dimensional stability explains the good natural durability. The heartwood is extremely resistant to treatment with preservatives, the sapwood is more permeable.

Bark and leaves are reportedly toxic to livestock. The bark contains tannin and produces a semi-translucent yellowish to reddish gum. A hydroethanol extract of the bark showed pronounced antioxidant and radical scavenging activity, with proanthocyanidins as the most likely active constituents. Twigs showed antimicrobial activity against a wide variety of bacteria and fungi; this supports the use as chewing-stick for dental care.

Adulterations and substitutes

The wood of Erythrophleum spp. and of Afzelia quanzensis Welw. resembles that of Burkea africana and is used for similar purposes.

Description

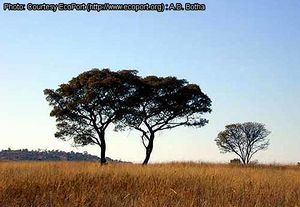

Deciduous small to medium-sized tree up to 20 m tall; bole branchless for up to 7 m, up to 80 cm in diameter; bark surface scaly and fissured, grey to dark greyish brown, inner bark fibrous, pink to dull red or purplish brown; crown open, often flat, with spreading branches; twigs thick, with conspicuous leaf scars, reddish brown hairy when young. Leaves alternate, clustered near the ends of twigs, bipinnately compound with (1–)2–5(–7) pairs of pinnae; stipules minute, soon falling; petiole and rachis together 7–32 cm long; petiolules 2–5 mm long; leaflets alternate, 5–15(–18) per pinna, usually elliptical, 1.5–7.5 cm × 0.5–4 cm, slightly asymmetrical at base, obtuse to slightly notched at apex, silvery short-hairy but becoming glabrous. Inflorescence an elongate spike 5–30 cm long, crowded near the ends of twigs, pendulous, many-flowered. Flowers bisexual, regular, 5-merous, sweet-scented, sessile; calyx with short tube and rounded lobes c. 1.5 mm long; petals free, obovate-oblong, 4–5 mm long, glabrous, white to cream-coloured; stamens 10, free, c. 5 mm long; ovary superior, ovoid, densely hairy, 1-celled, style short, stigma funnel-shaped. Fruit an elliptical, strongly flattened pod 3–8 cm × 2–3 cm, distinctly stiped, pale brown to reddish brown, indehiscent, 1-seeded. Seed ellipsoid, flattened, 9–12 mm × 7–8 mm, brown, with a cavity at both sides.

Other botanical information

Burkea comprises a single species. It seems related to the African genera Erythrophleum, Pachyelasma and Stachyothyrsus. When not flowering or fruiting, Burkea africana is often confused with Erythrophleum africanum (Welw. ex Benth.) Harms and Albizia antunesiana Harms, but it differs from both by its reddish brown velvety hairy young growing tips of twigs.

Anatomy

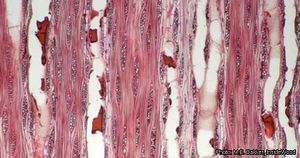

Wood-anatomical description (IAWA hardwood codes):

- Growth rings: 2: growth ring boundaries indistinct or absent.

- Vessels: 5: wood diffuse-porous; 13: simple perforation plates; 22: intervessel pits alternate; 23: shape of alternate pits polygonal; 26: intervessel pits medium (7–10 μm); 27: intervessel pits large (≥ 10 μm); 29: vestured pits; 30: vessel-ray pits with distinct borders; similar to intervessel pits in size and shape throughout the ray cell; 42: mean tangential diameter of vessel lumina 100–200 μm; 47: 5–20 vessels per square millimetre; 58: gums and other deposits in heartwood vessels.

- Tracheids and fibres: 61: fibres with simple to minutely bordered pits; 66: non-septate fibres present; 69: fibres thin- to thick-walled.

- Axial parenchyma: 80: axial parenchyma aliform; 81: axial parenchyma lozenge-aliform; 82: axial parenchyma winged-aliform; 83: axial parenchyma confluent; 85: axial parenchyma bands more than three cells wide; 86: axial parenchyma in narrow bands or lines up to three cells wide; (89: axial parenchyma in marginal or in seemingly marginal bands); 92: four (3–4) cells per parenchyma strand.

- Rays: 97: ray width 1–3 cells; 104: all ray cells procumbent; (106: body ray cells procumbent with one row of upright and/or square marginal cells); 115: 4–12 rays per mm.

- Mineral inclusions: 136: prismatic crystals present; 142: prismatic crystals in chambered axial parenchyma cells; (143: prismatic crystals in fibres).

(E.A. Obeng, P. Baas & H. Beeckman)

Growth and development

Rooting of Burkea africana trees is often superficial, and the roots can extend for many metres from the bole. Young trees reach sexual maturity when the bole diameter is about 12.5 cm. The inflorescences usually appear before the leaves, often at the end of the dry season. In southern Africa trees often flower in October–November and in West Africa in January–April. The flowers are pollinated by insects such as bees. It has been reported that trees fruit only once every two years. Fruits may remain for a long time on the tree, and are often still present after leaf fall.

Ecology

Burkea africana occurs in deciduous woodland and wooded savanna, at 50–1750 m altitude. The annual rainfall in its area of distribution is 1000–1200 mm. It is usually found on light, well drained soils, often on loose, sandy or gravelly red soils, but sometimes also on rocky hills or on loam-clay soils. In South Africa Burkea africana is often associated with Terminalia sericea Burch. ex DC. and Ochna pulchra Hook.f., and in Namibia with Colophospermum mopane (Benth.) J.Léonard, Combretum imberbe Wawra and Pterocarpus angolensis DC. Trees with a bole diameter above 12.5 cm are fire resistant, being sufficiently protected by their bark.

Propagation and planting

Burkea africana has a reputation for being difficult to cultivate. Seeds may germinate in 10 days, but may also take 6 months to germinate, and the germination rate is often low. Experiments in Burkina Faso showed that mechanical scarification or exposure to sulphuric acid for 15–20 minutes resulted in a significantly higher germination rate of seeds. Seeds can be stored for a long time in a dry place, but they are susceptible to insect attacks. It has been reported that seedlings often die off in the seed tray or when transplanted. However, experiments showed that if the seedlings are transplanted into a well-drained, sandy soil with superphosphate, the rates of survival can be quite high. Seedlings should be given 70–80% shade and water once every week. Red sandy soil gives the best results. Cuttings produce leaves and shoots that often soon die off.

Management

In many regions Burkea africana is common, locally abundant, but it usually occurs scattered and not gregarious. However, in southern Africa it can be dominant. Natural regeneration often occurs after fire. It has been noted that regeneration was good in natural stands in Namibia, both by seedlings and coppicing. The number of saplings per ha averaged 350.

Diseases and pests

A large proportion of the seeds is damaged by bruchid beetles. Porcupines have been recorded to damage trees seriously by scarring them, making them susceptible to fire damage. The foliage is consumed by caterpillars of several butterfly and moth species; Cirina forda has been classified as a pest.

Yield

A tree inventory in Namibia showed an average number of mature trees of 80 per ha and a mean wood volume of 16.5 m³/ha. However, the average yield of logs of good quality, i.e. 2 m long, straight and without defects, was only 0.05 m³/ha.

Handling after harvest

The centre of the bole is often defective. After harvesting for medicinal purposes, the bark is washed and air dried. When kept in airtight containers, it can be stored for 3–6 months. Bark decoctions are used immediately or stored in bottles for usage within one week.

Genetic resources

Burkea africana is not under threat of genetic erosion because it is widespread and common over large areas. However, in many regions natural stands have declined as a result of clearing for agriculture, changes in climatic conditions and soil salinity, excessive burning and locally also growing elephant populations. Systematic germplasm collection and specific preservation programmes do not exist, but there are small collections in botanical gardens, private gardens and research institutes in Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Prospects

The bole is usually of small size and this limits the use of the wood to smaller pieces of furniture and parquet blocks for flooring. If accessions developing large and straight boles would be available, Burkea africana might be interesting for cultivation as a timber tree because it yields high-quality timber. Research on silvicultural aspects would be required, as well as on propagation techniques and growth rates.

Burkea africana is a true multi-purpose tree, not only important for its timber but also as a source of medicine, firewood, dye and edible caterpillars, whereas its popularity as an ornamental tree is rising. As an important and widely used medicinal plant, it deserves more research on its active compounds, some of which have already shown interesting pharmacological activities.

Protection measures and domestication should be considered with a view to attain sustainable exploitation of this important African tree, which is being depleted at a quite high rate.

Major references

- Arbonnier, M., 2004. Trees, shrubs and lianas of West African dry zones. CIRAD, Margraf Publishers Gmbh, MNHN, Paris, France. 573 pp.

- Bolza, E. & Keating, W.G., 1972. African timbers: the properties, uses and characteristics of 700 species. Division of Building Research, CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia. 710 pp.

- Brummitt, R.K., Chikuni, A.C., Lock, J.M. & Polhill, R.M., 2007. Leguminosae, subfamily Caesalpinioideae. In: Timberlake, J.R., Pope, G.V., Polhill, R.M. & Martins, E.S. (Editors). Flora Zambesiaca. Volume 3, part 2. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 218 pp.

- Burkill, H.M., 1995. The useful plants of West Tropical Africa. 2nd Edition. Volume 3, Families J–L. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 857 pp.

- Dry, D., 1993. The wild seringa, Burkea africana. Veld & Flora 1993: 107.

- Mathisen, E., Diallo, D., Andersen, O.M. & Malterud, K.E., 2002. Antioxidants from the bark of Burkea africana, an African medicinal plant. Phytotherapy Research 16(2): 148–153.

- Neya, B., Hakkou, M., Petrissans, M. & Gerardin, P., 2004. On the durability of Burkea africana heartwood: evidence of biocidal and hydrophobic properties responsible for durability. Annals of Forest Science 61(3): 277–282.

- Palmer, E. & Pitman, N., 1972–1974. Trees of southern Africa, covering all known indigenous species in the Republic of South Africa, South-West Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. 3 volumes. Balkema, Cape Town, South Africa. 2235 pp.

- Takahashi, A., 1978. Compilation of data on the mechanical properties of foreign woods (part 3) Africa. Shimane University, Matsue, Japan, 248 pp.

- Wilson, B.G. & Witkowski, E.T.F., 2003. Seed banks, bark thickness and change in age and size structure (1978–1999) of the African savanna tree Burkea africana. Plant Ecology 167(1): 151–162.

Other references

- Adjanohoun, E.J. & Aké Assi, L., 1979. Contribution au recensement des plantes médicinales de Côte d’Ivoire. Centre National de Floristique, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. 358 pp.

- Adjanohoun, E.J., Adjakidjè, V., Ahyi, M.R.A., Aké Assi, L., Akoègninou, A., d’Almeida, J., Apovo, F., Boukef, K., Chadare, M., Cusset, G., Dramane, K., Eyme, J., Gassita, J.N., Gbaguidi, N., Goudote, E., Guinko, S., Houngnon, P., Lo, I., Keita, A., Kiniffo, H.V., Kone-Bamba, D., Musampa Nseyya, A., Saadou, M., Sodogandji, T., De Souza, S., Tchabi, A., Zinsou Dossa, C. & Zohoun, T., 1989. Contribution aux études ethnobotaniques et floristiques en République Populaire du Bénin. Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique, Paris, France. 895 pp.

- Aubréville, A., 1950. Flore forestière soudano-guinéenne. Société d’Editions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, Paris, France. 533 pp.

- Bossard, E., 1993. Angolan medicinal plants used also as piscicides and/or soaps. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 40: 1–19.

- Brenan, J.P.M., 1967. Leguminosae, subfamily Caesalpinioideae. In: Milne-Redhead, E. & Polhill, R.M. (Editors). Flora of Tropical East Africa. Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, United Kingdom. 230 pp.

- Burke, A., 2006. Savanna trees in Namibia - factors controlling their distribution at the arid end of the spectrum. Flora Jena 201(3): 189–201.

- Coates Palgrave, K., 1983. Trees of southern Africa. 2nd Edition. Struik Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa. 959 pp.

- Gelfand, M., Mavi, S., Drummond, R.B. & Ndemera, B., 1985. The traditional medical practitioner in Zimbabwe: his principles of practice and pharmacopoeia. Mambo Press, Gweru, Zimbabwe. 411 pp.

- Irvine, F.R., 1961. Woody plants of Ghana, with special reference to their uses. Oxford University Press, London, United Kingdom. 868 pp.

- Kpakote, K.G., Akpagana, K., De Souza, C., Nenonene, A.Y., Djagba, T.D. & Bouchet, P., 1998. Les propriétés anti-microbiennes de quelques espèces à cure-dents du Togo. Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises 56(4): 184–186.

- Leger, S., 1997. The hidden gifts of nature: A description of today’s use of plants in West Bushmanland (Namibia). [Internet] DED, German Development Service, Windhoek, Namibia & Berlin, Germany. http://www.sigridleger.de/book/. April 2003.

- Lewis, G., Schrire, B., MacKinder, B. & Lock, M., 2005. Legumes of the world. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 577 pp.

- Leyens, T. & Lobin, W., 2009. Manual de plantas úteis de Angola. Bischöfliches Hilfswerk Misereor, Aachen, Germany. 181 pp.

- Neuwinger, H.D., 2000. African traditional medicine: a dictionary of plant use and applications. Medpharm Scientific, Stuttgart, Germany. 589 pp.

- Steenkamp, V., 2003. Traditional herbal remedies used by South African women for gynaecological complaints. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 86: 97–108.

- van Wyk, B.E. & Gericke, N., 2000. People’s plants: a guide to useful plants of southern Africa. Briza Publications, Pretoria, South Africa. 351 pp.

- van Wyk, B. & van Wyk, P., 1997. Field guide to trees of southern Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa. 536 pp.

- Watt, J.M. & Breyer-Brandwijk, M.G., 1962. The medicinal and poisonous plants of southern and eastern Africa. 2nd Edition. E. and S. Livingstone, London, United Kingdom. 1457 pp.

- Williamson, J., 1955. Useful plants of Nyasaland. The Government Printer, Zomba, Nyasaland. 168 pp.

- Zida, D., Tigabu, M., Sawadogo, L. & Oden, P.C., 2005. Germination requirements of seeds of four woody species from the Sudanian savanna in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Seed Science and Technology 33(3): 581–593.

Sources of illustration

- Brenan, J.P.M., 1967. Leguminosae, subfamily Caesalpinioideae. In: Milne-Redhead, E. & Polhill, R.M. (Editors). Flora of Tropical East Africa. Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, United Kingdom. 230 pp.

- Coates Palgrave, O.H., 1957. Trees of Central Africa. National Publications Trust, Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia. 466 pp.

- Palmer, E. & Pitman, N., 1972–1974. Trees of southern Africa, covering all known indigenous species in the Republic of South Africa, South-West Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. 3 volumes. Balkema, Cape Town, South Africa. 2235 pp.

Author(s)

- A. Maroyi

Botany Department, Rhodes University, Box 94, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa

Correct citation of this article

Maroyi, A., 2010. Burkea africana Hook. [Internet] Record from PROTA4U. Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Louppe, D. & Oteng-Amoako, A.A. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. <http://www.prota4u.org/search.asp>.

Accessed 22 December 2024.

- See the Prota4U database.