Erythrophleum ivorense (PROTA)

Introduction |

| General importance | |

| Geographic coverage Africa | |

| Geographic coverage World | |

| Stimulant | |

| Dye / tannin | |

| Medicinal | |

| Timber | |

| Fuel | |

Erythrophleum ivorense A.Chev.

- Protologue: Vég. util. Afr. trop. Franç. 5: 178 (1909).

- Family: Caesalpiniaceae (Leguminosae - Caesalpinioideae).

Vernacular names

- Ordeal tree, sasswood tree (En).

- Lim du Gabon, tali (Fr).

- Mancone (Po).

Origin and geographic distribution

Erythrophleum ivorense occurs from Gambia to the Central African Republic and Gabon.

Uses

The bark traded as ‘sassy-bark’, ‘mancona bark’, ‘casca bark’ or ‘écorce de tali’ has several medicinal uses. A bark extract is taken orally in Sierra Leone as an emetic and laxative, and is applied externally to relieve pain. In Côte d’Ivoire water, in which the bark of young branches of Erythrophleum ivorense is crushed, is rubbed on the skin to treat smallpox.

The bark and sometimes the seeds are widely used as hunting and ordeal poison. In Liberia and Gabon the bark of Erythrophleum ivorense is preferred to that of Erythrophleum suaveolens (Guill. & Perr.) Brenan. The bark is used as fish poison in Sierra Leone.

The timber of Erythrophleum ivorense is marketed as ‘erun’, ‘missanda’, ‘sasswood’, ‘alui’, ‘bolondo’ or ‘tali’. The wood is quite hard and heavy, and suitable for joinery, flooring, railway sleepers, harbour and dock work, turnery, construction and bridges. It is also used for boat building and wheel hubs. It makes excellent charcoal and good firewood. In Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire the bark is used for tanning. A bark decoction added to fermenting palm wine would make it a more potent drink.

Production and international trade

In trade statistics, the timber of Erythrophleum ivorense and Erythrophleum suaveolens is usually not differentiated. In 2005 the export of Erythrophleum (‘tali’) logs from Cameroon amounted to 37,500 m3 and of sawn wood to 38,600 m3, which made Erythrophleum the fourth most important timber of Cameroon. In 2005 the price of logs free-on-board was US$ 123–151/m3, depending on the quality. The major importer is China.

Properties

The alkaloid content of Erythrophleum ivorense is similar to that of Erythrophleum suaveolens; only the distribution of the main compounds is different. First investigations yielded the alkaloid erythrophleine, but this was later identified as a mixture of different alkaloids with similar activities. The alkaloids are esters of tricyclic diterpene acids, and 2 main types exist: dimethylaminoethylesters and monomethylaminoethylesters (nor-alkaloids). In addition, compounds have been found in which the amine link is replaced by an amide link, but it is not clear whether these are natural compounds or artefacts. The bark contains as main components alkaloids of the dimethylaminoethylester type: cassaine, cassaidine and erythrophleguine, but no dominant alkaloid of the amide type. The alkaloid content of the bark ranges from 0.2% to 1.1%. In high doses, the bark extract is an extremely strong, rapid-acting cardiac poison, in warm-blooded animals causing shortness of breath, seizures and cardiac arrest in a few minutes.

The alkaloids have a stimulant effect on the heart similar to that of the cardenolides digitoxine (from Digitalis) and ouabain (from Strophanthus gratus (Wall. & Hook.) Baill.), but the effect is very short-lasting, as the alkaloids are quickly metabolized in the organism. Cassaine and cassaidine have strong anaesthetic and diuretic effects, and increase contractions of the intestine and uterus. Apart from an increase of heart contraction in systole, the alkaloids also demonstrated an increase in diastole. In addition, cassaidine caused depressive effects, while cassaine caused a violent state of excitation. Although the alkaloid content in the seeds is markedly lower than in the stem bark, the seeds are more toxic. This strong activity is due to a strong haemolytic saponin, which acts in a synergistic way with the alkaloids.

Wood from Erythrophleum ivorense and Erythrophleum suaveolens is not differentiated in trade and the following wood description is applicable to both species.

The heartwood is yellowish brown to reddish brown, darkening on exposure, sometimes striped, clearly demarcated from the 3–6 cm wide, creamy-yellow sapwood. The grain is interlocked, texture coarse. The wood is moderately lustrous.

The density is about 900 kg/m3 at 12% moisture content. The wood dries slowly with high risks of distortion and checking. The shrinkage rates from green to oven dry are 5.1–5.8% radial and 8.4–8.6% tangential. Once dry, the wood is moderately stable in service.

At 12% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is 99–162 N/mm2, modulus of elasticity 10,550–19,500 N/mm2, compression parallel to grain 56–97 N/mm2 and Janka side hardness 13,000 N.

The wood is difficult to saw; stellite-tipped sawteeth are recommended. Finishing is generally fair, but planing may be difficult due to interlocked grain. Pre-boring is necessary for nails and screws. The gluing properties are good.

The wood is durable and resistant to fungi, dry wood borers and termites. It is suitable for use in contact with the ground. It is not permeable for preservatives. The sawdust may irritate mucous membranes and may cause allergy and asthma of labourers in sawmills.

Adulterations and substitutes

Erythrophleum alkaloids have similar pharmacological activities as digitoxine and ouabain. The timber from Erythrophleum ivorense and Erythrophleum suaveolens is marketed indiscriminately under the trade names: ‘tali’, ‘erun’, ‘bolondo’ and ‘alui’. The timber of Pachyelasma tessmannii (Harms) Harms resembles that of Erythrophleum, hence the trade name ‘faux tali’. Erythrophleum wood can be used as a substitute for azobé (Lophira alata Banks ex P.Gaertn.).

Description

Large tree up to 40 m tall; bole cylindrical, but sometimes fluted at base, with or without buttresses; bark scaly, often fissured, grey, inner bark reddish, granular; young twigs brown hairy. Leaves alternate, bipinnately compound with 2–4 pairs of pinnae; stipules minute; petiole 2–7 cm long, rachis 5–15 cm long; leaflets alternate, (6–)8–14 per pinna, elliptical to ovate, up to 8.5 cm × 4 cm, base asymmetrical, apex shortly acuminate. Inflorescence an axillary or terminal panicle consisting of spike-like racemes up to 8 cm long, shortly reddish brown hairy. Flowers bisexual, regular, 5-merous, red-brown; pedicel c. 1 mm long, shortly hairy; calyx c. 1.5 mm long, lobes c. 0.5 mm long; petals narrowly obovate, c. 2 mm × 0.6 mm, densely hairy; stamens 10, free, 2–3.5 mm long; ovary superior, long woolly hairy, 1-celled, stigma broadly peltate. Fruit a flat, elliptical, dehiscent pod 5–10 cm × 3–5 cm, base rounded, apex obtuse or rounded, thick leathery, pendulous, 2–6(–10)-seeded. Seeds ovoid, compressed, c. 13 mm × 9 mm × 5 mm.

Other botanical information

Erythrophleum comprises about 10 species, 4 or 5 of which occur in continental Africa, 1 in Madagascar, 3 in eastern Asia, and 1 in Australia. The genus is one of the few Caesalpiniaceae reported to contain alkaloids. Erythrophleum ivorense and Erythrophleum suaveolens share many uses, vernacular names, trade names and properties and therefore confusion is common. Especially the results of earlier pharmacological work are blurred by doubtful identifications. The 2 species differ in ecology, some morphological characteristics and the alkaloid profile in the bark. Only in semi-deciduous forest does Erythrophleum ivorense co-occur with Erythrophleum suaveolens, from where the latter extends into drier habitats like woodland savanna. However, it is often difficult to distinguish the two species from each other. The leaflets of Erythrophleum suaveolens are often wider, its inflorescences wider (often 1.5 cm versus 1 cm in Erythrophleum ivorense) and its pods longer.

Anatomy

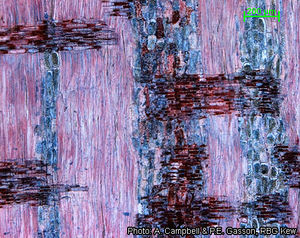

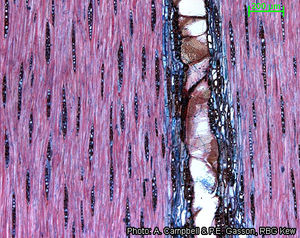

Wood-anatomical description (IAWA hardwood codes):

- Growth rings: (1: growth ring boundaries distinct); (2: growth ring boundaries indistinct or absent).

- Vessels: 5: wood diffuse-porous; 13: simple perforation plates; 22: intervessel pits alternate; 23: shape of alternate pits polygonal; 26: intervessel pits medium ( 7–10 μm); 29: vestured pits; 30: vessel-ray pits with distinct borders; similar to intervessel pits in size and shape throughout the ray cell; 43: mean tangential diameter of vessel lumina ≥ 200 μm; 46: ≤ 5 vessels per square millimetre; 47: 5–20 vessels per square millimetre; 58: gums and other deposits in heartwood vessels.

- Tracheids and fibres: 61: fibres with simple to minutely bordered pits; 66: non-septate fibres present; 69: fibres thin- to thick-walled; 70: fibres very thick-walled.

- Axial parenchyma: 79: axial parenchyma vasicentric; 80: axial parenchyma aliform; 81: axial parenchyma lozenge-aliform; (83: axial parenchyma confluent); (84: axial parenchyma unilateral paratracheal); 91: two cells per parenchyma strand; 92: four (3–4) cells per parenchyma strand; (93: eight (5–8) cells per parenchyma strand).

- Rays: (96: rays exclusively uniseriate); (97: ray width 1–3 cells); 104: all ray cells procumbent; 115: 4–12 rays per mm; 116: ≥ 12 rays per mm.

- Mineral inclusions: (136: prismatic crystals present); (142: prismatic crystals in chambered axial parenchyma cells).

Growth and development

Erythrophleum ivorense flowers during the rainy season. Nodulation was observed in primary rainforest and the rhizobium involved belongs to the genus Bradyrhizobium. In Côte d’Ivoire the mean annual bole diameter increment has been recorded as 6.5 mm, in the Central African Republic 4.5 mm.

Ecology

Erythrophleum ivorense occurs in evergreen primary and secondary forest and moist semi-deciduous forest. Erythrophleum ivorense is essentially a tree of old secondary forest.

Propagation and planting

Erythrophleum ivorense has been classified as a non-pioneer light demander. Seedlings are often found in smaller forest gaps. Erythrophleum ivorense can be propagated in nurseries; seed takes 3 weeks to germinate. Inoculation with Bradyrhizobium is beneficial and results in increases in height and diameter of about 40% after 4 months.

Management

Erythrophleum ivorense trees usually occur scattered in the forest. In Gabon the average bole volume has been recorded as 1.4 m3/ha. In Liberia the mean density of trees with a minimum bole diameter of 60 cm is 0.7 tree/ha. Reforestation with Erythrophleum ivorense is an option in degraded forests where natural regeneration of economically important species is unlikely. In Gabon the clear-cut method is superior to enrichment planting: 6 years after planting the survival rate was 97% vs 79%, the height 16 m vs 11 m and the bole diameter 13.6 cm vs 6.8 cm for the 2 methods respectively.

Harvesting

Old Erythrophleum ivorense trees very often have heart rot. The bark of Erythrophleum ivorense is harvested from the wild whenever the need occurs.

Handling after harvest

The logs sink in water and can consequently not be transported by floating along a river.

Genetic resources

Erythrophleum ivorense is often abundant in West and Central African evergreen forest. Although logging of Erythrophleum ivorense for its timber has shown a distinct increase in Cameroon, there are no indications that the species is under too much pressure yet.

Prospects

Erythrophleum ivorense contains pharmacologically interesting compounds and further study of its pharmacology is justified. Internal use of unpurified medicines made from Erythrophleum ivorense is extremely dangerous. The differences in active ingredients between individual trees in a single population and the differences in composition related to age of the plant are large. Although Erythrophleum ivorense has recently gained much importance as a timber tree, especially in Cameroon, comparatively little is known about proper management practices for sustainable harvesting in natural forest.

Major references

- Aubréville, A., 1959. La flore forestière de la Côte d’Ivoire. Deuxième édition révisée. Tome premier. Publication No 15. Centre Technique Forestier Tropical, Nogent-sur-Marne, France. 369 pp.

- Aubréville, A., 1968. Légumineuses - Caesalpinioidées (Leguminosae - Caesalpinioideae). Flore du Gabon. Volume 15. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France. 362 pp.

- Burkill, H.M., 1995. The useful plants of West Tropical Africa. 2nd Edition. Volume 3, Families J–L. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 857 pp.

- Chudnoff, M., 1980. Tropical timbers of the world. USDA Forest Service, Agricultural Handbook No 607, Washington D.C., United States. 826 pp.

- CIRAD Forestry Department, 2003. Tali. [Internet] Tropix 5.0. http://tropix.cirad.fr/ afr/tali.pdf. May 2006.

- Cronlund, A., 1976. The botanical and phytochemical differentiation between Erythrophleum suaveolens and E. ivorense. Planta Medica 29(2): 123–128.

- de Saint-Aubin, G., 1963. La forêt du Gabon. Publication No 21 du Centre Technique Forestier Tropical, Nogent-sur-Marne, France. 208 pp.

- ITTO, 2004. Annual review and assessment of the world timber situation. International Timber Trade Organisation. Yokohama, Japan. 255 pp.

- Neuwinger, H.D., 1996. African ethnobotany: poisons and drugs. Chapman & Hall, London, United Kingdom. 941 pp.

- Richter, H.G. & Dallwitz, M.J., 2000. Commercial timbers: descriptions, illustrations, identification, and information retrieval. [Internet]. Version 18th October 2002. http://delta-intkey.com/wood/index.htm. May 2006.

Other references

- Bakarr, M.I. & Janos, D.P., 1996. Mycorrhizal associations of tropical legume trees in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Forest Ecology and Management 89(1–3): 89–92.

- Diabate, M., Munive, A., Miana de Faria, S., Ba, A., Dreyfus, B. & Galiana, A., 2005. Occurrence of nodulation in unexplored leguminous trees native to the West African tropical rainforest and inoculation response of native species useful in reforestation. New Phytologist 166(1): 231–239.

- Durrieu de Madron, L., Nasi, R. & Détienne, P., 2000. Accroissements diamétriques de quelques essences en forêt dense africaine. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 263(1): 63–74.

- Hegnauer, R. & Hegnauer, M., 1996. Chemotaxonomie der Pflanzen. Band 11b-1. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland. 500 pp.

- Hogberg, P. & Alexander, I.J., 1995. Roles of root symbioses in African woodland and forest: evidence from 15N abundance and foliar analysis. Journal of Ecology 83(2): 217–224.

- InsideWood, undated. [Internet] http://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/search/. May 2007.

- Koumba Zaou, P., Mapaga, D., Nze Nguema, S. & Deleporte, P., 1998. Croissance de 13 essences de bois d’oeuvre plantées en forêt Gabonaise. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 256(2): 21–32.

- Siepel, A., Poorter, L. & Hawthorne, W.D., 2004. Ecological profiles of large timber species. In: Poorter, L., Bongers, F., Kouamé, F.N. & Hawthorne, W.D. (Editors). Biodiversity of West African forests. An ecological atlas of woody plant species. CABI Publishing, CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 391–445.

- Sprent, J., 2005. West African legumes: the role of nodulation and nitrogen fixation. New Phytologist 167: 321–323.

- Voorhoeve, A.G., 1979. Liberian high forest trees. A systematic botanical study of the 75 most important or frequent high forest trees, with reference to numerous related species. Agricultural Research Reports 652, 2nd Impression. Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen, Netherlands. 416 pp.

Sources of illustration

- Voorhoeve, A.G., 1979. Liberian high forest trees. A systematic botanical study of the 75 most important or frequent high forest trees, with reference to numerous related species. Agricultural Research Reports 652, 2nd Impression. Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen, Netherlands. 416 pp.

Author(s)

- C.H. Bosch, PROTA Network Office Europe, Wageningen University, P.O. Box 341, 6700 AH Wageningen, Netherlands

Correct citation of this article

Bosch, C.H., 2006. Erythrophleum ivorense A.Chev. In: Schmelzer, G.H. & Gurib-Fakim, A. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 23 December 2024.

- See the Prota4U database.